The second installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

A month after a failed protest at the college president’s office, I got a chance to prove myself as a radical activist leader. Our group consisted mainly of students. Marxist doctrine and common sense told us students are never going to overthrow capitalism. In the hope of broadening the movement, we had been cultivating ties with campus workers, and it was one of these allies who gave me my chance.

Big Mike, a janitor, was one of our strongest supporters. A genial, broad-shouldered, mountain of a man with scraggly black hair, he always had a smile for me when he came into the snack bar where I worked most afternoons. One day, though, there was no smile. After paying for his order, he beckoned me out from behind the grill. Roger the mechanic, his buddy, was in trouble.

“They’re trying to fire him,” he said in a stage whisper. “Can you guys help?”

Could we ever! What better chance to show our support for workers could we possibly hope for? I filled in Bruce, and he agreed that I should call Roger that night and meet with him as soon as I could.

At Roger’s house the next morning I sat down with him and his wife Shirley and he told me his story. According to him his infraction was trivial—not working fast enough on repairs to some kind of machinery—but they were really going after his job, and the union had done nothing to help him.

My mind raced. There was no time to lose. I had to get him in front of a large group of students, and quickly. What about the snack bar at lunch time? Would Roger stand up there and tell his story? He looked hesitant, but Shirley said sure he would, and she’d be there to tell her side of it too. We sat down at the kitchen table to write up the account for flyers we would pass out.

I was apprehensive about going to Bruce with the plan. As leader, he should have been consulted before I made any commitment. To my relief, he found no fault, even agreeing we should keep the details secret in case, as we suspected, there was an informer among us.

The snack bar seating area was a large space, about half the size of a basketball court. At noon the tables were packed to overflowing and conversation was boisterous. I’d sold revolutionary newspapers here a few times before work to a pretty heterogeneous crowd of students, mostly friendly except for a big group of fraternity members who congregated at tables near the jukebox.

On the day of the rally we moved quickly, making the most of every precious second before the campus police shut us down. A couple of SDS members distributed flyers while Big Mike and I set up our rented sound system. Roger and Shirley huddled in a corner waiting for the rally to start. I wondered if they were intimidated by the noise and the large crowd. Roger wasn’t that outgoing. He had a ponderous, awkward way of speaking. Would either of them have the poise and confidence to stand up and tell their story? Would anyone even be able to hear them over the hubbub?

Amazingly, by the time we were ready to start no cops had appeared yet. I turned on the sound system, blew into the microphone, and heard the roar of my breath clearly over the crowd noise. No need to worry about whether people could hear us. I started to talk about what had happened to Roger and who was responsible: college administrators. Having worked with Bruce nearly two months now, I knew my lines backwards and forwards. These fascist exploiters screwed workers and supported the war by allowing military recruiters on campus. They paid professors to spread racist, anti-working class lies. Now they had the gall to fire a family man in his fifties because he didn’t work fast enough.

This was Roger’s cue. He lumbered up to me, took the microphone, and stood there shifting his weight from foot to foot as if uncertain what to do next. Standing in the doorway where I kept watch for the cops, I hardly dared breathe. Conversation had died down while I spoke, and now heads turned toward us as people waited to hear what Roger would say.

He looked out over the crowd and took a deep breath.

“I work in Buildings and Grounds,” he said at last. His speech was halting, but as he went on he seemed to gain confidence and the words came more easily. He explained that the bosses wanted everyone to work faster. But speed-up was dangerous. Speed-up caused accidents. Speed-up caused injuries.

About the time he said “injuries,” somebody jeered from the fraternity tables and a half dozen of his friends laughed. A big bruiser with a crew cut got up and slid a coin into the jukebox. A country western song started to play at full volume. Roger looked over at me. I looked at Bruce. Bruce looked at the frat boys. There must have been 20 of them, and there were only five of us, not counting Roger and Shirley.

We had a plan for informers. We had a plan for the cops. But we had no plan for the frat boys. Big Mike did, though. More quickly than I’d ever seen him move before, he squeezed through the crowded tables, bent down by the jukebox, and pulled the plug.

Silence.

The fraternity boys stared at Big Mike. He stood by the machine with his arms folded, plug in hand. One of the fraternity ring-leaders opened his mouth to say something. Big Mike looked at him and he shut it again.

When Roger was done, his wife Shirley strode over and took the microphone. Loudly and angrily, she described what it was like to pay bills with no paycheck coming in. She talked about what it felt like worrying how they were going to make the next mortgage payment. I leaned back against the door jamb, caught up in her story. Shirley was a natural. All the kids were transfixed. I was transfixed. A couple of months ago I wouldn’t have dreamed this was possible. I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that I—a reserved, introspective kid who’d dropped out of an Ivy League college—was the catalyst who had brought all this about.

Bruce spoke last—the clean-up hitter. To my relief, he kept it short. No long lecture about Marxism. He focused on workers. Their fight was our fight, he said. Not just on the RIC campus, but all over Providence, all over the U.S., all over the world. And that included the Vietnamese workers and peasants fighting the military machine of U.S. imperialism.

By the time the cops came he was done. We shut off the sound system before they could get to it. Minutes later, our supply of leaflets was exhausted and the sound system packed into the trunk of Bruce’s beat-up old Volvo. Standing behind the serving counter at the start of my shift that afternoon, I could barely contain my elation. Everything had worked like clockwork—from the leaflets and sound system to the big crowd to Big Mike at the jukebox to Shirley dishing out a dose of real life to all those naive college kids. I’d made an impact. I’d advanced the cause of the workers. For the first time, what we were doing was working. The sense of triumph I felt validated PL and communism more than any argument or debate. It never occurred to me that what Roger and Mike had told me wasn’t the whole story. In our world the workers’ story was the whole story. Everything else was just ruling-class lies.

For a few hours the success was intoxicating, but I wasn’t prepared for the aftermath. I doubt even Bruce could have predicted it. He claimed afterward he wasn’t surprised and I halfway believed him. Despite my reservations about Bruce and his leadership, I was still inclined to accept communist doctrine. It hadn’t occurred to me yet that the self-serving arrogance I sometimes thought I detected in Bruce might be symptomatic of something widespread among radical activists, still less that if I looked in a mirror, I might see it there too.

When I called Roger the next day to talk about next steps, Shirley said he wasn’t able to come to the phone. I called again in the afternoon. There was no answer. A few more times I tried with no luck. Then Big Mike heard from a fellow worker that the union had found Roger a job with a different employer. So he didn’t have to fight for his job. Neither did that do-nothing union, Bruce pointed out. And, of course, the price of the new job was Roger’s silence.

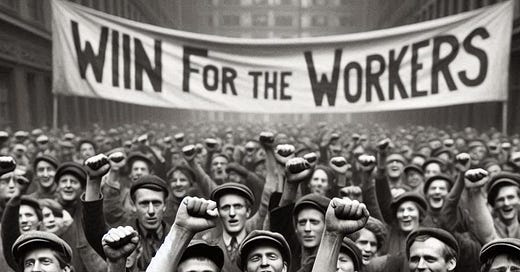

I couldn’t help feeling betrayed, but when I told Bruce, he grinned reassuringly and told me not to be sophomoric. Sure, it’s a pain in the ass when union goons interfere with your plans, but this wasn’t personal. This was a win for the workers. We’d exposed the do-nothing union. Now they were rushing to cover their tracks. If we could see that, wouldn’t the workers see it too? That’s how you build trust. That’s how you build militancy. Multiply it ten thousand times and spread it across fifty states and you’d have a working-class movement the ruling class was no match for.

For once Bruce’s confidence reassured me. In spite of Roger’s defection, we’d salvaged something from the snack bar rally. Someone somewhere was taking us seriously and working overtime to blunt the effects of our militance.

It didn’t occur to me then to wonder who that someone might be. I assumed it was some union official or other. If anyone had suggested a broader coordinated effort to limit our influence, I think at this point I would have been skeptical. And if anyone had been so bold as to suggest God had a hand in it, I would have laughed. In my humanist worldview, man was the measure of justice. From the point of view of the self-absorbed 20-year-old activist, man meant me. If a being beyond us existed, He would have had to be on the side of the bloody upheaval we were trying to provoke. More to the point, He would have had to be on my side for leading it.