A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

In the summer and fall of 1970, my stock in the radical activist movement in Providence was rising. For six months I’d been working with the Progressive Labor Party (PL), a communist group committed to the overthrow of the government and the destruction of capitalism. Working with PL was a far cry from being a member. You didn’t just sign up for membership. You worked for months or years to prove your commitment and to satisfy Party leaders that you weren’t a police informant.

In the fall of 1970, I was invited to join a special class for candidate members of the Party. I was thrilled when Bruce, the local leader in Providence, told me the news. I’d passed the test. This was my encounter with destiny. A life of glorious struggle for justice opened up before me. It felt like I was walking on air.

PL at that time was near the height of its national influence, with a few thousand members concentrated mainly in New York, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco. Small for a national protest organization, but what mattered wasn’t its size but the quality, commitment, and discipline of its members. Compared to other left-wing groups—the Black Panthers, the Youth International Party (Yippies), the Weathermen, etc.—PL received very little publicity, but it worried government leaders enough to prompt an investigation by the House of Representatives Committee on Internal Security, culminating in a 700-page report that names, among hundreds of others, me and 4 other members of the candidates’ class which began in the fall of 1970. I wasn’t aware of this report at the time, but discovering it 50 years later, I was stunned to discover such a voluminous chronicle of our machinations.

The candidates’ class was led by Caleb, a member of the PL national committee and head of the large New England area party apparatus. We met in his apartment in a working-class section of Boston. Every other week that fall and winter, I drove up there with Emily, Bruce’s girlfriend, who had also been admitted to candidacy.

Though only in his mid-twenties, Caleb seemed a lot older than me and most of the other candidates. We were undergraduates. He’d earned a bachelor’s degree from Harvard and was rumored to have dropped out of its graduate program in philosophy. He was married to a social worker, also a Party member. They had a child. In addition to his role as Party leader, Caleb worked in a factory, evidently a Party directive. Marxist doctrine held that factory workers would lead the proletarian revolution. Everyone, leaders included, were expected to immerse themselves in the working class. I didn’t know how Caleb balanced work, fatherhood, and Party leadership, which required travel to New York once a month. But I did know that I couldn’t have.

The class met on a weekday evening in a triple-decker apartment building in a working-class Boston neighborhood. I was very impressed by the surroundings: the old wooden buildings marching uphill along a narrow street lined with cars; Caleb’s cramped apartment; the battered, utilitarian furniture; the air of secrecy.

Caleb revealed little about himself, but his world-weary demeanor spoke volumes. A leader of the student take-over of a Harvard administration building the previous spring, he’d been targeted by police, university officials, and local prosecutors. It was pretty obvious that the struggle and its legal repercussions had worn on him—not to mention the burden of manual labor and Party leadership, which included, of course, leading our group of neophytes. Early on, I was awed by the presence of someone who had given so much for the cause.

Brief glimpses of family life reinforced the impression of dedication and sacrifice. Every so often a harried, determined-looking woman with a short hair cut would slip quietly through the back of the room, carrying a child and a bag of groceries. Once when she went out an errand, the child was deposited in Caleb’s arms, and I can still remember the sweet song he sang softly to her to the tune of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude”:

Hey girl, Don’t let me down. Sing a sad song And make it better. For you know That soon the workers will win. Then we can begin To make it better.

The workers never did win, at least not on our terms. For that I am now deeply grateful.

Despite my favorable early impressions of Caleb, I was not enthralled by our class meetings. I had expected to learn more about the origins, development, and doctrine of the Party, the history of imperialism, and secret new capitalist schemes that must be percolating all over the world. Instead discussion focused mainly on us, the settings we worked in, and what we were doing to recruit workers and working-class students.

PL at the time was faced with a quandary. It called itself the vanguard of the working class, the cutting edge of revolution that would one day guide workers to power. In fact, however, it was composed mainly of idealistic college students and ex-students. How was this motley crew to embed itself among factory workers, win their trust, and eventually maneuver them into positions of revolutionary leadership? And so our slogan became “Build a Base in the Working Class”—something we wouldn’t have had to do if there were more actual workers among us.

In practice building a base meant two things. The first was finding more opportunities to sell newspapers, pass out leaflets, and get into political discussions with working-class people. The idea was not just to argue or distribute literature but to get people’s names and then follow up with them, bring them to meetings, and gradually draw them into the PL net.

I had already been doing this for 6 months. I thought of myself as one of the most reliable members of the Rhode Island group, but I became painfully aware that other candidates far surpassed me. They proposed all kinds of strategies that had never occurred to me: sitting down next to someone on a bus and selling them a PL newspaper, or striking up a conversation with the next person in line at the DMV. The theme of these discussions was that you are hardly ever alone in life. Any time someone else is within earshot, that is an opportunity for winning them to the cause.

At first this “anytime, anywhere” approach intrigued me. I liked to think of myself as always ready for the next round of struggle. In practice, though, I couldn’t keep it up from morning to night. Even in classes, when I was on guard for professors to say something I could object to, I treasured my down time when I could just sit there and not argue. The sad but unavoidable truth was, I needed time to myself. I soon realized that it would be best not to reveal this. Judging from how the group reacted to qualms voiced by others, a craving for solitude would likely be viewed as a bourgeois trait that any true activist must strive to eradicate. Dedication to the cause was supposed to be all-consuming.

The other aspect of basebuilding was developing relationships that went beyond politics. To win someone to the Party you had to get to know them. You had to become a part of their lives. This side of basebuilding was more to my taste. I had, after all, recruited Eileen, the timid young art student, and now we were as much part of each others’ lives as any two people could be. Unfortunately “part of their lives” wasn’t supposed to stop with your girlfriend. As far as I could make out, there was no end to it. As much as I had enjoyed visiting Roger, the fired campus worker we held the rally for, I couldn’t envision him becoming a close friend. I had no problem chatting with Big Mike the janitor when he came in the snack bar, but bowling with him or going out for a beer?

The problem was you couldn’t say no to this kind of suggestion. Awkward, personal, even intimate questions would be sure to follow. Do you think you’re better than ordinary working-class people? Are you unconsciously living your life by middle-class norms? Have you succumbed to a bourgeois “fear of the people”?

The others took challenges like this in stride, but I found them annoying. All of us in the group had college degrees or were working on getting them. Several went to private colleges. There was even a Harvard philosophy professor, Alisdair. Just going out for a beer with this or that worker wouldn’t make people like Alisdair or the rest of us part of the lives of working-class people. Middle-class revolutionaries carried their outlook with them wherever they went. Listening to them talk, you could tell they still thought of themselves as upwardly mobile, destined for a comfortable home and a white-collar job. Sitting in a bar surrounded by workers wouldn’t change that.

I’d been thinking a lot lately about middle-class revolutionaries. I was one now, but would I always be?

That fall, instead of moving back into the college dorm, I had rented a room in a dingy rooming house on the south side of town. The principal reason for the move was for privacy with my girlfriend Eileen, but my new quarters soon took on a far larger significance.

Life there was very different from dorm life. The rooming house was populated by transients, people down on their luck, and impoverished elderly. At first they were surprised to see someone like me coming and going, but gradually the novelty wore off. Little by little, I was learning to be there without attracting attention. There is a special contentment that comes with living where no one knows who you are or where you come from. In bed at night, with the door locked, I felt a sense of peace in the conviction that my past, my upbringing, and my middle-class origins could never reclaim me.

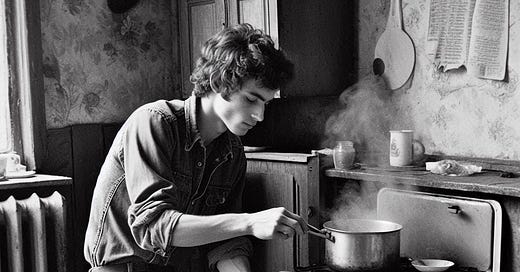

Part of the transformation involved Eileen. Many a night after classes, we’d stop at a store, pick up a cheap cut of meat, and cook together on the battered old gas stove. Afterward we’d have an hour or two left before it was time to drive Eileen home for Ma’s curfew.

Alone together in that dingy room, we would talk about things never mentioned at school during the day. Things about Ma and her father and what it was like growing up. Pa drank a lot, and he had a temper. Eileen used to hide in the bedroom with Josie, her younger sister. You could hear dishes crash. Even now that he was gone, Eileen would still hear that sound in her dreams. Driving back after dropping her off at Ma’s tiny apartment, I used to marvel at how different this was from dating at my former Ivy League college, where girls there kept you at arm’s length with their talk about courses and vacations and college classmates.

In the deep of winter, Pa died in a work accident, and Eileen felt a huge sense of relief, tinged with guilt. On those dark nights when she and Josie hid in the closet, she’d prayed secretly for God to take him away, and now she was responsible for the end of a life, for Ma’s grief, and for the whole family’s poverty.

I tried to reassure her no one would blame her for wanting the violence and terror to end. When she couldn’t accept that, I offered the Party’s materialistic philosophy: that the unseen being she prayed to didn’t exist. There was no possible connection between prayer and anything that happened in the real world, including the death of her father. You can’t kill someone by wishing or praying.

In the eerie silence, she lay still in my arms thinking about this. Every so often, when the wind blew or someone shifted in bed, you could hear the old house groan. That was what it was like living there, alone together in a sea of filth and despair, with our separate lives slowly fading and merging into this new reality we were going to create together.

This transformation, I came to believe, was what it took to make a better and more just world—not bean counting and contact lists. The banal chatter in candidates class about selling papers on buses washed over me but left me unmoved. However much they talked about revolution and the rule of the working class, they were who they’d always been.

Little by little, without me even noticing, the Party I’d once longed to join slipped into second place in my life, runner up to a personal journey to I knew not where. Ever so slowly, despite my assurances to Eileen that God didn’t exist, I was learning lessons that I now realize He must have set for me.