A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

Radical activists seek to tear down society and tradition. When Eileen and I were married in the spring of 1972, we were no exception. In our circle, an important test of authentic commitment was for your personal life to mirror how you wanted to remake society. For us, that principle would have ruled out a conventional honeymoon even if we could have afforded one.

We did, however, want to celebrate being married. Since we both enjoyed travel, we reasoned that a low-budget trip to an urban working-class destination would accomplish this goal within the constraints of both our budget and our principles. We had a friend in New Orleans—Celeste, whom we met at Georgia State and tried to recruit to the communist movement. She’d since graduated and moved back to her hometown. She was eager to have us come and see her if we traveled that way.

Our battered Volkswagen, a sleeping bag, and an electric frypan—what more did radical activists need for a road trip in the early 1970’s? Instead of a tent, we brought along a tarp and clothesline, which we hoped would keep us reasonably dry if it rained. Somewhere in Alabama, we stopped at a park for the night and strung up the tarp between two trees at the top of a hill. Dinner was a bottle of cheap wine, bread, cheese, and a couple of hard-boiled eggs from the dozen we’d brought with us.

Curling up together in the sleeping bag, we fell asleep almost at once, content in knowing we’d allowed ourselves no luxury that poor people couldn’t afford. Imagine our puzzlement when we woke up the next morning, heads wet with dew, having rolled out from under the tarp and halfway down the hill into long grass while we were sleeping!

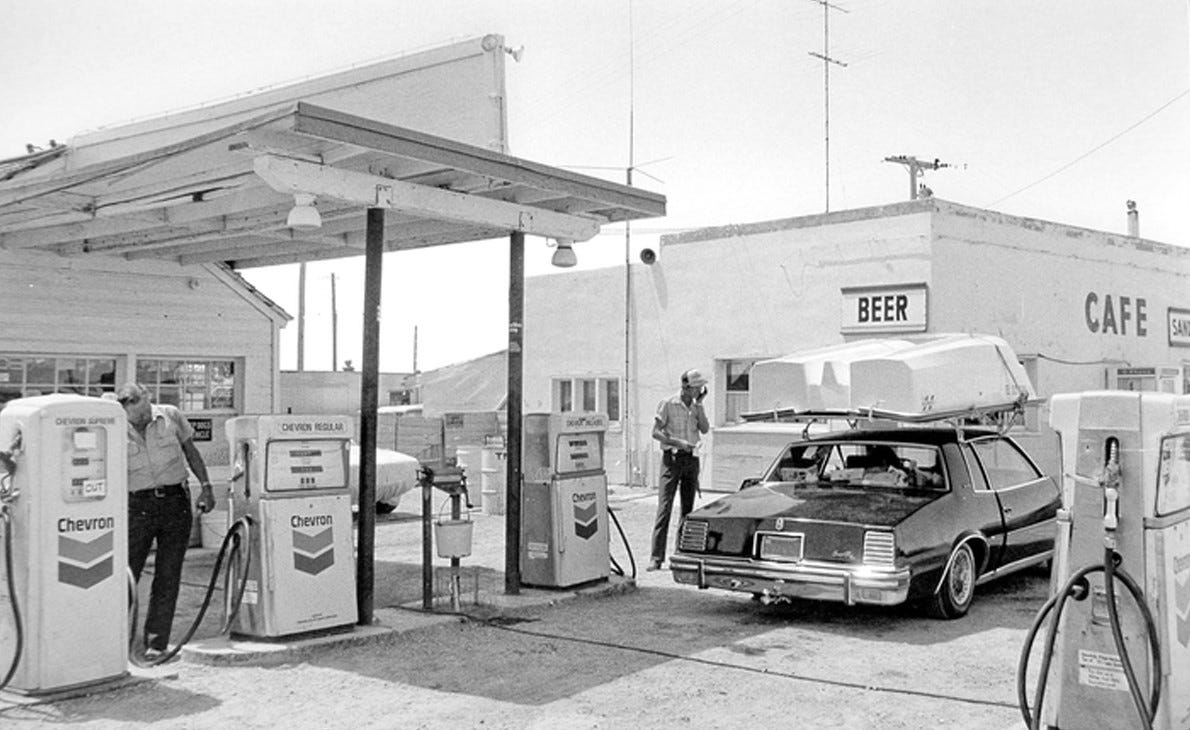

That morning the bread was growing stale, the cheese and the eggs just a tiny bit slimy, but no matter. Come the revolution when provisions were scarce, and we’d eat food like this gratefully. The one creature comfort we weren’t yet prepared to forego was coffee. It didn’t cost much at the little café adjoining the gas station where we stopped to fill up the Volkswagen, so we sat down and treated ourselves.

It was an exotic location—rural south Alabama, faded curtains and just a few chipped Formica-top tables. The kind of place where seasoned communist organizers ought to feel right at home, but we felt like foreigners. A couple of good old boys at the next table were playing poker. From their sidelong glances, I guessed they were sizing us up. After some murmured comments, the one with his back to us put down his cards, pushed his chair back, and lumbered outside. One of his buddies called me over. Wouldn’t I pick up the hand and keep the game going? Their friend had already anted up and raised them once, and it would be a shame to let his stake go to waste.

I couldn’t think of a good reason not to. Best to fit in with the locals, try to be one of the guys. I sat in for a few hands, won one and lost a few more. Then the friend who had left returned. I felt rather than saw him behind me. The eye movements of the other players subtly changed. What was going on here? How would I even know if signals were passed? I caught Eileen’s eye. She had already paid for the coffee. We got out of there as fast as we could, leaving the good old boys grumbling behind us. I’d lost two dollars. Two dollars we couldn’t afford. Afterward, though, I reflected that it could have been a lot worse. Two dollars was a small price to pay for escaping without further harm.

We had planned to sleep outside in New Orleans. There were campsites in a state park on the north shore of Lake Ponchartrain, an easy commute to the city. It didn’t occur to me at age 22 that the woods near the Gulf Coast would be nothing like those I was used to in New England.

Arriving after dark, we set up the tarp and prepared to settle in for the night. No sooner had we slid into the sleeping bag than the mosquitos attacked. Zipping the bag shut over our heads did nothing to stop them. Sitting in the Volkswagen with the windows up didn’t help either.

You would have thought hard-core communist revolutionaries could have toughed out one night like this. Not us. Exasperated, cursing Louisiana and everything in it, we packed up and fled south through the city. After driving for over an hour, we found an empty parking lot in a deserted industrial area. No mosquitos. Making sure our doors were locked, we tilted our seats back and slept fitfully until dawn.

I didn’t like having to admit that camping had failed, but a glance at Eileen’s red eyes and sweat-streaked forehead told me there was no alternative but to find a motel. Not one of the cute ones in the French quarter where a night cost a month’s rent, let alone the grandiose big-name hotels downtown where parking would have consumed our whole budget. The Triple A city map I’d brought along gave no hint where we’d find anything cheaper, so we drove through down-market commercial districts, up one street and down another as the sun rose in the sky and sultry hot air blew in the open car windows.

It was afternoon before we found a budget motel, a one-story ell-shaped building with a postage-stamp parking lot. It cost way more than I’d planned on spending, but we’d only go on our honeymoon once, and after nearly two full days without shelter, we had no real alternative. The room was cramped and dark, but the air conditioner worked and it was a huge relief to be out of the glaring sun. I could tell from the way Eileen stretched out on the bed that she felt it too. That night we shopped in a grocery store for provisions and cooked a hot meal in the electric fry pan. It tasted wonderful.

Radical activists aren’t tourists. We didn’t need a capitalist guidebook to tell us what to see and not see. Avoiding better-known sites that attracted out-of-town visitors, we focused instead on neighborhoods that would give us a feel for the daily life of the city.

Over the next few days, walking, driving, listening and gazing and smelling, we took in the distinctive flavor of New Orleans. In the damp heat, the dull thud of traffic, and the music of voices, I felt a peaceful anonymity which reminded me of the first weeks I moved off the college campus and lived in one small, dingy furnished room in a building populated by transients. Humdrum, workaday New Orleans was, in its way, just as exotic as the smelly, down-at-the-heel clientele I had rubbed shoulders with there. Its streets were more than an urban maze to be navigated in search of life’s necessities; they hinted at heroism and a transformed future.

Tracing the rows of small shotgun-style houses up and down scorching streets, I found myself daydreaming of the lives that unfolded here and what it would be like if ours was one of them. The commercial districts with their faded signs and rattling air-conditioners brooded in the fierce sun, as if waiting to be swept up in the communist uprising. Would it come sooner if more people like us moved here? It wouldn’t be a bad place to live. Exploring grocery stores, we found seafood and greens never seen in Atlanta. Bookstores, too, had a local flavor and offered happy hours of uninhibited browsing. I found a discounted copy of the Times-Picayune Cookbook which I carried for many years afterward, reminding me of those sultry, languid early days of our marriage.

We had written in advance to Celeste, and she had asked us to dinner. We found her small house on a shady street, a modestly upscale version of the streets we’d been exploring. Instead of a dusty, dried-up patch of lawn, she had actual greenery—shrubs and a few flowers that looked like they’d been recently watered.

In a small living room we sat on wicker chairs under a ceiling fan. Celeste served us iced tea and insisted we tell her all about our wedding and what we’d seen so far in New Orleans.

Eileen spoke volubly about the wedding: what she wore, the delicate diplomacy between our two families, our apprehension about how they would react to our comrades. To my relief she didn’t mention the cheap motel I’d found that had made her mother and sister so miserable. We hadn’t spoken of that since the wedding. I sensed it was still a sore point for Eileen.

When we turned to New Orleans, however, conversation flowed less freely. Celeste was puzzled that we hadn’t visited any real landmarks. Though interested in the movement, she wasn’t herself a radical activist, and it was hard to explain why we weren’t ticking off the usual tourist sights.

I tried to explain what intrigued us about the neighborhoods and stores we’d explored, but I could see I wasn’t making much headway. I looked to Eileen for support, thinking she might have better rapport with Celeste. She didn’t say much. For the first time I wondered if she was as engrossed in what we’d seen together as I was. We’d been together a couple for two years now, and as far as I knew we shared the same aspirations: activism, self-denial, a modest standard of living. It was hard to imagine someone who truly embraced that perspective giving in to the enticements of a middle-class lifestyle.

There was something in particular I wanted to find out from Celeste. I had heard you could buy healthful blackstrap molasses in bulk very cheaply at New Orleans sugar refineries, but I had no idea where to look. Celeste explained where the refineries were located. The next day I suggested trying to find them. Eileen hesitated at first, then said she’d rather I went by myself. That worried me. I thought it would be an adventure finding molasses. Should I not go? Was there something she’d rather do? I asked her. She just shrugged. She’d be all right on her own for a few hours.

When I came back, she was sitting on the bed, waiting for me so we could get food for dinner. She didn’t seem at all interested by the five gallon cans of molasses I’d managed to buy for a pittance or in the lengths I’d gone to in obtaining them.

A few days later, leaving New Orleans early in the morning so we could get back to Atlanta in time for school the next day, we took a scenic coastal route, hoping to explore a small town or two and maybe a beach or a state park. We didn’t talk much, but after a while Eileen seemed to be engrossed in the scenery and I got the impression she enjoyed taking back roads. The tension I’d started to feel at Celeste’s house and in the days afterward eased a bit.

Because we’d left so early and stuck to back roads, we didn’t find anywhere open to eat till we were well out of New Orleans, approaching Pass Christian, Mississippi. There, on the outskirts of town, we found a tiny family-owned bakery just opening. We stopped and went inside. There was no real breakfast available, but Eileen liked my idea of economizing by buying one whole jelly roll to share with our coffee.

Smiling at our thrift, the woman who served us asked where we were from. Hearing that this was the first time we’d seen Pass Christian, she settled herself against the counter to tell us about Hurricane Camille, which had swept over the tiny community several years earlier. Hundreds of people had lost their homes. Some of her neighbors were still rebuilding. The bakery was flooded and had to stay closed for months till the damaged equipment could be replaced and the building dried out and refurbished. The Baptist church she attended had been turned into rubble. For some weeks they’d had to hold services in a parking lot until a high school opened its gym to them. Little by little, relying mainly on volunteer labor, the church was being rebuilt and would open its doors again soon.

It was a mournful tale, but also strangely sweet and loving. Her melodic voice, infused by the morning sunlight that filtered through dusty air from the front window, filled the quiet interior of the shop with a lovely resonant sadness. It never occurred to me that the way she spoke to us and the effect of her voice on me might have something to do with her being a Christian. I merely thought to myself, this is what you find when you travel back roads, another one of those exotic locations conventional tourists never discover.

Paying our check, I felt a little twinge of regret at leaving so soon, mixed with anxiety about the subtle but unmistakable gap between Eileen and me. It would have been nice to stay here in the bakery and listen to sweet stories of rebuilding that town a few minutes longer. Years later, recalling what happened between Eileen and me, I often find myself thinking about the bakery and that welcoming voice, melodious with what I now know is the spirit of Christ. Something in that voice filled me with a mysterious yearning, which with the passage of years was to grow steadily clearer and stronger.