Forgiveness

A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

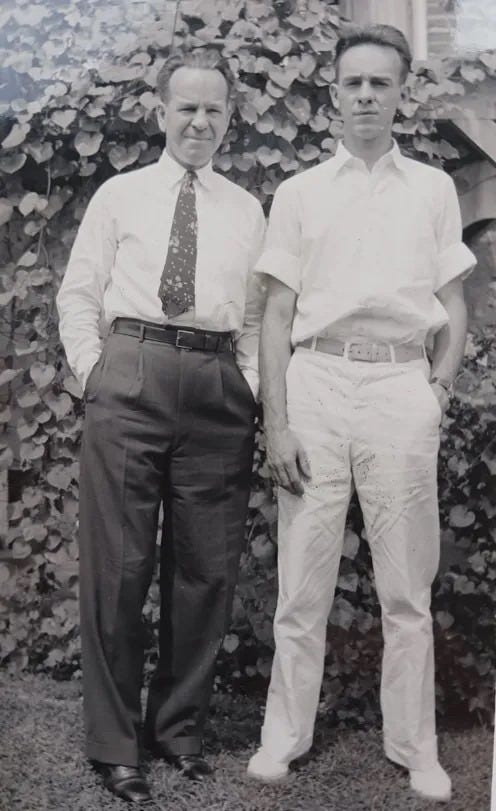

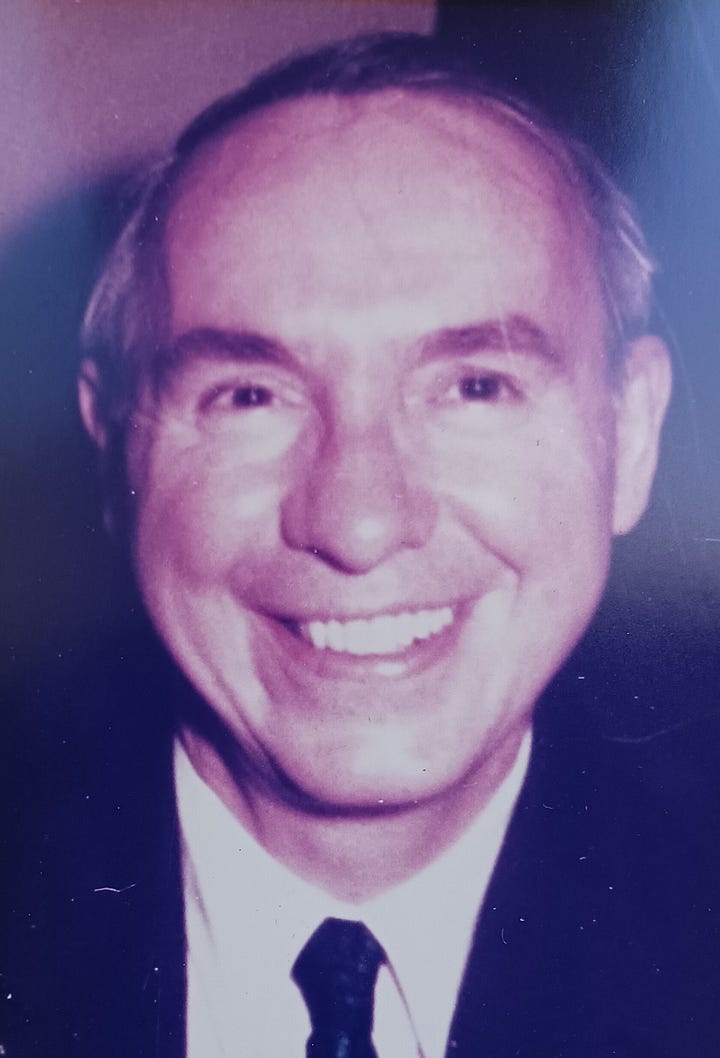

In the spring of 1976, in my third year of teaching, my father, by then Vice President of John Hancock Life Insurance, attended a company conference in Atlanta where I was living. We arranged to spend the weekend together afterward. Though I looked forward to the visit, I worried for several weeks about how I was going to entertain him. My father didn’t like traveling. He didn’t like leaving behind his books and records and tennis and squash evenings to spend time in surroundings that didn’t appeal to him.

It didn’t help that relations between us had been extremely tense for several years. He’d been outraged when I took a leave of absence from Harvard during my sophomore year. He claimed that the paralyzing anxiety I felt was a ruse to disguise indolence. He was even angrier a year later, when I decided to enroll in a small state college. My plan to become a teacher, he alleged, was a pretext for communist organizing.

I did not take this well. Even though I really was a communist organizer, I was perfectly serious about becoming a teacher. His real problem, I told him, was not that I was deceitful, but rather that I had set out to destroy the society that enabled our family to live in luxury while others had nothing. He didn’t like hearing that, but I took an unwholesome delight in making sure he would never forget it.

Now that I had become a teacher and given up communist organizing, hostility between us had cooled, but I was painfully aware that he wouldn’t approve of the way I was living. I owned no car. I lived in a modest apartment overlooking a parking lot and a city bus stop. My teaching job in an inner-city elementary school would never lead to advancement. I thought of it as the perfect opportunity to promote social justice, but I doubted he’d see it that way. I could only imagine him muttering to my mother afterward about how I was wasting my talents.

Despite all this, I was looking forward to seeing my father, and I welcomed the challenge of making this awkward visit enjoyable. Before his arrival, I spent several nights cleaning up my bedroom, dumping stray possessions in the small room I used for an office, and washing sheets so he could sleep on my mattress and box springs. On Friday, the last day of his conference, I took the day off, rented a car, bought groceries I thought would be more to his taste than what I usually ate, and drove across town to pick him up outside the conference hotel. In spite of the fact I was late, he seemed happy to see me. We shook hands, and he didn’t complain that I’d kept him waiting in brutal heat for 45 minutes.

I led a pretty solitary life in those days. I’d lost touch with most of my college friends. Having renounced radical activism, I’d been ostracized by former comrades. I didn’t think of myself as lonely, but not having close friends did make it difficult to know what to do with my father.

On the night of his arrival, I enlisted the aid of my neighbors, the apartment manager and her husband. I didn’t have much in common with them, but they’d been kind to me—invited me to play cards and brought me to church with them once. They agreed to share a meal with my father and me. It wasn’t exactly a convivial evening—the social distance was too great for that—but everyone tried. I don’t know how successful I was in reproducing the beef and string bean stir fry my mother made at home, but my father at least tolerated it, and to the best of my knowledge no one got sick afterward. All things considered, there were plenty of worse ways my father and I could have spent our first night together.

I knew my father enjoyed fishing, so for the next day I planned an excursion to Lake Lanier, an hour north of the city. I’d called ahead and confirmed you could rent a boat and fishing tackle and purchase fishing licenses. We didn’t catch anything—not even a nibble. After a couple of hours the wind picked up, and the placid lake turned choppy. I was relieved when my father suggested we head for shore, and even more relieved when we actually got there.

A second excursion went more smoothly. I lived close to Stone Mountain—15 minutes by bus. On weekends I occasionally hiked there, climbing the bald face of the small mountain and exploring wooded trails below. It was a treat to be able to drive there and not have to wait for the bus.

It was a beautiful morning, already warm when we arrived, and my father enjoyed the shade of the trails that ran along the base of the mountain. Crossing a small bridge over a brook, he paused and asked if I’d fished there. When I admitted I hadn’t, he promised to send me some of his fishing tackle. It arrived a few weeks later. I made the trip out to Stone Mountain, found the brook we crossed, and spent an hour casting and doing my best not to snag the line. Returning to my apartment without fish, later than planned, I thought wistfully of the pleasure my father wished for me. Painful as it was to admit to myself, I liked Stone Mountain better when I went there unencumbered.

The one serious glitch in my plans for that weekend was that my friend Jim was otherwise occupied. Jim had grown up in foster care. During the first few years I’d known him, he’d been estranged from his biological father, but in the past year they’d made contact. I’d spent many hours with the two of them, watching them try to rebuild their relationship. I was curious to see what Jim would make of my father, and vice versa.

Because Jim wasn’t available, I decided to take my father to meet his foster parents, the Harmons, who lived in a small cinderblock house far out in the country. It was they who had urged Jim to get back in touch with his father. In retrospect taking my own father to meet them that morning seems like an odd thing to do, but by then I’d been over to their house with Jim several times, and Mrs. Harmon had told me I was welcome to come on my own any time.

Driving out through corn and cotton fields in the humid spring air, I had a hard time gauging my father’s reaction. He seemed preoccupied. I wondered if it was with the landscape or my driving. Although I knew generally where we were headed, the route wasn’t as familiar as I had expected, and I wished I’d paid closer attention when I went out there with Jim. It hadn’t occurred to me that I’d ever have a reason or an opportunity to drive here on my own.

At last I found the dusty back road that led to our destination. I slowed down, hoping to shrink the unsightly cloud of dust that billowed behind us. Mrs. Harmon must have heard our approach, because she stood outside waiting. I spotted her husband Roy peering out at us through the screen door.

I wasn’t sure what our reception would be like, but Mrs. Harmon put to rest any worries on that score, making a huge fuss over my father and how pleased she was that I had brought him.

Roy, too, in his gruff way, seemed to appreciate that something unusual was happening. Sitting down at the table, we sipped the coffee Mrs. Harmon poured for us. Roy gave my father a long, appraising look, and then asked if he and I could come back next month. Friends from church were coming over to help slaughter the hog. They’d need all the help they could get.

My father raised his eyebrows in surprise. I couldn’t help smiling. I was pretty sure he’d never seen a hog slaughtered or even known anyone who had. This was what I’d brought him to see: the plainspoken warmth of ordinary working-class people, the directness of someone who’d spent their lives without the education and privilege that had surrounded me every day of my life till I dropped out of Harvard. The Harmons didn’t care where we’d come from or what subjects we’d studied in college. To them we were just plain folks like their church friends.

The Harmons were people of faith, born-again Christians. I didn’t see anything significant about that at the time. I just thought of them as people with colorful stories and a unique outlook on the world. Roy did not ask my father how often he read the Bible, as he did me on my first visit, but I did get him to admit he was a lay preacher. When I steered the conversation to his prison ministry, he spoke passionately about convicts’ tears as they begged God for forgiveness

My father listened patiently, taking it all in. I’d noticed the night before with our dinner guests that he had a knack for expressing polite interest in whatever anyone said to him, without disclosing any real feeling. That was how he reacted to the convicts’ remorse, and that, too, was his response when Mrs. Harmon handed us the bowl of scraps and sent us around the back of the house to fatten the sow for the knife next month. That was his attitude when we returned to the kitchen, where a plate of steaming biscuits awaited us.

It didn’t surprise me. I’d seen my father in enough social situations to recognize and understand his guarded approach to the world. Whoever he dealt with outside of the family, he kept his feelings in check and his thoughts to himself. That had been his counsel to me all through childhood and adolescence. As a child I had submitted reluctantly. In my teens, I bristled. When I left Harvard I left it behind me. It was a bad way to live. Superficial politeness worked well enough in some situations, but as a rule of life it was crippling. It was a sure way to guarantee no one knew you.

That day, in the Harmons’ sultry kitchen, I reflected that my father’s reserve was pretty much par for the course, but I wanted more from him. On the way back to town, I asked what he thought of the Harmons.

He hesitated before answering, and I braced myself for more evasion, or even for a critical answer.

“That old man,” he said at last, “reminded me of my father.”

I glanced over at him. This wasn’t the answer I had expected. I’d hoped for something specifically related to Roy Harmon, something about his unusual life story or entertaining anecdotes or even his distinctive pattern of speech. Despite my disappointment, though, I had to admit my father had spoken with feeling, even if exactly what the feeling was wasn’t clear to me.

My grandfather, whom we called the Colonel in recognition of his Army career, had died a few years before. He’d been living in southern Georgia. I traveled down there for the memorial service, and sat with him and my aunt and my grandfather’s widow when the local pastor came to offer condolences. It was a tender memory—one of the few times I had seen my own father vulnerable.

He’d always had an uneasy relationship with the Colonel. The tension between them had been a staple of Christmases and other family gatherings all through my childhood. I guessed at some level he must have yearned for reconciliation. It hadn’t occurred to me that visiting Roy Harmon, a man of the same generation, might remind him that he would never attain what he longed for.

On Sunday afternoon, when it was nearly time for us to leave for the airport, he suggested we call my mother in Boston and say hello. It was a brief call. I didn’t think much about it at the time. I just told my mother the visit had gone well, thinking we’d talk about the details when she called the next week. Then my father got on the phone to remind her of the details of his flight.

He seemed subdued when we set out for the airport. We drove a few miles in silence, and then out of the blue he asked me,

“How did she seem to you?”

Something in his tone caught my attention. I shot him a puzzled glance.

“How did she seem?”

“Your mother.”

What was he getting at? She sounded pretty much as she always had. I’d talked to her only a minute or so, and he not much longer.

“She seemed sort of sad on the phone,” he explained.

I was surprised. It was very unlike him to say something like this. It was extremely rare for him to refer to emotion—his own or anyone else’s.

“She always seems sad after she talks to you.”

To me? Really? I remember feeling an intense pang of emotion but not being able to put a name to it. Tears may have welled up in my eyes. I didn’t trust myself to speak. I had this overwhelming impression that my father hadn’t said quite what he wanted to say. It wasn’t my mother’s sadness he was describing. It was his own.

Looking back now, all these years later, I marvel at my reaction to this brief exchange. The hours with Jim and Elmer had had their effect on me. Instantaneously and painfully, I had a powerful sense of my father’s love for me. After years of acrimony between us, the idea that he might actually miss me was heartbreaking, the more so because he could never have brought himself to say it directly.

It was as close as he ever came to forgiving me all the trouble I’d caused.

The closest I came to forgiving him for the trouble and pain he caused me was to move north at the end of that school year and agree, at his suggestion, to live in the old farmhouse in Maine he’d bought as a ski lodge. He loved that. He loved having me back in New England and under his roof again.

My homecoming came none too soon.

The following summer, a little more than a year after he visited me in Atlanta, my father was diagnosed with leukemia. He died six months later.

Looking back years afterward, I marvel at the timeliness of the olive branch he offered when we spent the weekend together. But it was not just the olive branch, it was also everything I had done that led up to accepting it—putting radical activism behind me, breaking ties with my comrades, and most of all accompanying Jim on night visits to warehouses and office buildings where his father worked as a security guard. I had watched them there, week by week, repairing the damage done by estrangement, gradually relinquishing the burden of blame and guilt for their separation. Having seen them do that, I understood how I should respond to my father’s entreaty. It wasn’t solely my own doing that I responded in the way that I did. It was a response that had been prepared for me long in advance. All I had to do was give into the feeling that welled up inside me.

When I accepted Christ four decades later, I realized God had been at work in my life for a long time. The startling juxtaposition of events all those years ago didn’t just seem miraculous, it actually was His hand steering me toward a destination I couldn’t see for myself. No human agency could have planned the confluence of those three families—Jim’s foster family, his biological family, and mine.

In the spring of 1976, though, I was a long way from that realization. I had progressed a step or two away from radical activism toward acceptance of Christ, but the path that would eventually lead me there was a long and tortuous one.