A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

It’s a terrible thing to be married and feel your spouse drawing away, especially during the first months of marriage. You find yourself grasping at straws. Each tiny thread of connection floods you with hope that you can hold on, even as the thing you wanted desperately to preserve starts slipping away again.

That was what I was feeling in the summer of 1972, when Eileen and I flew up from Atlanta to visit my parents in Massachusetts. Recently they’d had a house built on Cape Cod in anticipation of my father’s retirement, and we would stay there for a few days and hopefully spend some time at nearby beaches. It was a potentially awkward situation. Eileen and I were radical activists pledged to tear down the comfortable middle-class world my parents inhabited. In the past few years there’d been many ugly scenes between my father and me. I didn’t know what to expect this time.

I felt a flicker of regret when we drove up to the pleasant Cape-Cod style house with white trim and raw shingles slowly darkening in the salt air at the end of a wide drive of crushed shell. This was the world from which I’d exiled myself when I became a communist two years earlier. If we stayed true to our principles, we would never be able to afford a house like this. Even so, I could see that Eileen admired it. Was she having second thoughts about the life we had planned?

By the time we unpacked the dinner hour was approaching. My father made drinks, and we sat in the living room while he described his gardening and landscaping projects: dwarf fruit trees, composting bins, a large fenced vegetable garden. It felt odd to sit there, sipping my drink, listening to this tale of middle-class privilege and occasionally interjecting a question or two. I didn’t challenge my father for building his wealth on the backs of the workers. We’d been down that path too many times in the past. I realized now it led nowhere. For his part, he didn’t ask about my progress in college or whether communist organizing interfered with my studies. There was no need. He’d already given me a deadline of December, after which there would be no more tuition support. That took the pressure off both of us. Even though I knew deep down this détente was ephemeral, I had a sense we could sit talking like this for a long time without acrimony.

After we chatted a while, Eileen went out to the kitchen to help with dinner. I put a few more polite questions to my father about fertilizer and fruit trees and then followed her. A modern oak table at one end had already been set for the meal. Eileen stood at one end of the counter, chopping string beans and sweeping the tips into the sink. When she finished, my mother suggested the two of us walk down to the sound while we waited for the roast to be done. An upper-middle-class meal, I thought wryly. A roast, not a casserole.

We crossed the drive and ambled fifty yards or so down to where the paved road gave way to a dirt track that led to the water’s edge. It was a beautiful evening. The sun warmed our backs, and a light breeze blew in from the water.

“She didn’t say anything about how I did the string beans,” said Eileen as we looked out over the water.

“The string beans were fine.”

I said it too quickly, probably with a hint of impatience. I could tell from the way she avoided my eyes this wasn’t what she wanted to hear. She was anxious about my parents accepting her. She’d grown up poor and felt out of place. I kept insisting that what my parents thought didn’t matter. Come the revolution, there’d be no more middle class. Just the plain workers. Everyone else would be reeducated and assigned to manual labor. But, as she’d reminded me more than once, the revolution hadn’t come yet. Rich and poor still did matter. In an ideal world no one would care, but right now people still did.

I tried reasoning with her.

“You washed them, trimmed them, and cut them to size. That’s all she wanted.”

“Would she tell me if she didn’t like how I did them?”

Probably not, I thought. A couple of years before, I’d brought a different girl home. She, too, helped my mother with string beans, but she refused to cut off the tips—the most nutritious part, she explained. They shouldn’t be wasted. Nobody said anything, but I heard plenty about it after she left.

Eileen wouldn’t like hearing that, so I didn’t say anything. We walked a little way along the sandy shore of the cove, not speaking. Her anxiety was beginning to grate on me, but when we turned back, the moment of tension seemed to have passed. A few minutes later we sat down to our roast beef and wine and vegetables and blueberry pie. It was a good meal, and I was incredibly hungry. No one who saw me then would have guessed I had a subversive bone in my body.

The days that followed passed like a dream, full of sun and beach visits and yard work and leisurely breakfasts by the French windows looking out over a steadily growing patch of my father’s vegetable garden. I drove the riding mower and took a turn with my father’s new rototiller. The sun and the physical work felt good, but I had this gnawing sense that this wasn’t where I belonged. I should be back in the South, organizing a movement that would smash all this privilege.

Eileen, too, slipped peacefully into the vacation routine. Her nervousness gradually melted. She didn’t ask again whether my mother approved of her. Without any hint of anxiety, she went off with her to the butcher and the produce stand and the wine shop. Like the rest of us she brought something to read at the breakfast table. You would have thought she’d been around us all of her life. I was so thankful. It was a like a switch between us had been flipped and everything was all right again, at least for these few tranquil days of vacation.

My mother used to tease my younger brother Archbold and me about how much she wished one of us had been a girl so she could buy clothes for her. Now that Eileen was part of the family, she was determined to make the most of the opportunity. One morning she mentioned there was an outlet store a half hour away and asked if Eileen needed any new clothes. The answer surprised me. A winter coat. It was the middle of summer. I thought of the tattered parka she wore on cold days in Atlanta, a relic of high school. She’d never complained about it, and it hadn’t occurred to me that she might want to replace it.

On the last day of our visit, off they went to the outlet shop. When they returned in the mid-afternoon, Eileen was holding an expensive-looking calf-length Kelly-green wool coat— utterly incongruous with the rest of our life. Where would she wear it? But when she put it on and asked how it looked, I had to agree it was stunning. Later, several years after we were divorced, Eileen called my mother and confided that she had been the best part of our marriage. When I heard that I thought of the Kelly-green coat and those few halcyon days on Cape Cod when it actually looked like she was becoming part of the family.

After the visit to my parents, Eileen and I had arranged to travel to Miami for the Democratic National Convention. Myriad activist groups from around the country were gathering there either to celebrate the nomination of George McGovern as Democratic candidate for president or to protest the Democratic Party’s resistance to his progressive agenda. McGovern opposed the Vietnam war and pledged to bring all U.S. troops home. He supported national health care, a guaranteed annual income, and passage of the Equal Rights Amendment to guarantee equal pay for women.

Our group, the Progressive Labor Party, denounced McGovern as a hypocrite and a fraud. We claimed he was a tool of the capitalist ruling class, and his reforms were a ploy to pacify workers and curb rising militance. Nothing short of revolution to smash capitalism could truly change the country. That was the message we and our communist brothers planned to take to Miami.

To save money on plane fare, we had arranged to drive for a commercial car transport service. In Boston we picked up a company car bound for Miami. Setting out in mid-afternoon, we drove all night and through most of the next day. It was a strangely peaceful journey, just the two of us cocooned in this luxurious, powerful Oldsmobile, propelling us forward from one life to another. Eileen and I talked sporadically for an hour or so, then fell silent, watching the acres of pavement empty out ahead of us as the light faded and evening edged into night.

Parting from my parents had been painful but also exhilarating. As always in transit between my former life and the new one forged in rebellion, I had this strange sense of shuttling between two worlds, and I could almost feel myself turning from one person into another. For however long the journey took, I was suspended in a kind of no man’s land where past and future converged.

That night, as we hurtled south on empty highways, I would have been surprised to learn what the next few years held in store for me: the end of my marriage; reconciliation with my parents; drifting away from radical activism; eventually a decisive break from the Party and all that it stood for.

When we live in the present, we think of ourselves as being in charge of our lives, but I had no idea at the time where I was headed. Later, when we consider how things turned out from some vantage point far in the future, we realize that our plans and decisions often lead in directions we haven’t anticipated. I did not will the rapprochement with my parents, the end of my marriage, the fading of my political zeal, or the loss of my comrades. Small actions—talking with my father about his fruit trees, shutting off the conversation with Eileen about string beans, admiring the Kelly-green coat even though it didn’t fit our lifestyle—pointed toward a journey I would never have envisioned in the summer of 1972. No human being can predict, let alone guide, where all the myriad small decisions that make up our lives will lead. There is, however, someone who does guide and predict. At age 23, I was a long way from knowing Him, but when I look back now over the course of my life, I can see clearly where and how he was leading me.

After 25 hours of travel, interrupted only by brief stops for food, gas, and rest rooms, Eileen and I arrived in Miami Beach in simmering late afternoon heat. The car wasn’t due for delivery till Monday, so we drove directly to the park where demonstrators were gathering. Other Party members had already arrived. They had set up a small tent with a folding table in front, where we were greeted with armfuls of literature. We were exhausted and dazed, but the revolution never pauses for down time. We were immediately put to work passing out flyers promoting a protest against McGovern, Democrats, and bourgeois reformism.

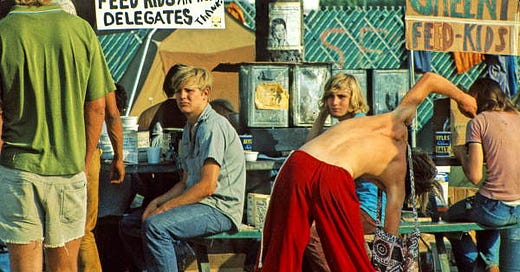

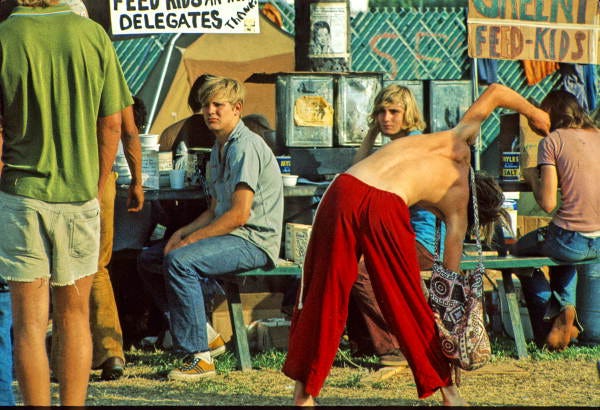

It was a thankless task. Nobody wanted to hear the harsh doctrine of our little Party. As the crowd grew more boisterous, our meager efforts were drowned out in the excitement. The throng was caught up in music, political theater, and the cries of hawkers. Smells of fried food from vendors mingled with odors of sweat, beer, and marijuana. In the festival atmosphere, no one wanted to get into a debate about whether McGovern or the Democrats were sincere or served some shadowy cabal of capitalist rulers.

By dusk the small quantum of energy we’d initially mustered had deserted us. Glancing guiltily at one another, we ditched what remained of our flyers and gave ourselves over to sightseeing, trusting the chaos would shield us from comrades looking to put us to work again. Threading our way among makeshift tents and tables, we browsed the literature of fringe groups like the Yippies and the Pot People’s Party, ogled beads and tattoos and weird hairdos, and lounged in an open area to listen to a couple of guitar solos and a humorous political skit.

When it was dark we left the park in search of somewhere quiet to eat. On a side street we discovered a tiny Cuban-Chinese restaurant squeezed into a store front. Hunched over one of the two small tables, we gorged on mounds of pungent squid and yellow rice. Trudging back to the park, almost asleep on our feet, we held hands and I thought how delicious it was being alone together in the midst of this tumult. It felt like the early days of our intimacy back in Rhode Island, before Eileen left home, before the abortion, before marriage, before the hurt silences. At the edge of the park we spotted a grassy spot shielded by a bench from the park lights. We got our sleeping bag from the car, crawled into it, and fell into a deep and contented sleep in each others’ arms.

In the morning, alas, contentment vanished. We woke up in full sun, bathed with sweat. Changing clothes in the back seat of the Oldsmobile was a contortionist act. After breakfasting with comrades on dry doughnuts and instant coffee out of a thermos, we went off to distribute more leaflets. By the light of day the other demonstrators were more actively hostile. All of our arguments for discipline and class struggle fell on deaf ears. Everything we said seemed to rub someone in this big, unruly crowd the wrong way.

The sun made the ordeal worse. By noon Eileen’s normally pale cheeks were pink, tinged with scarlet. We hadn’t thought to bring sunscreen. After a lunch break, we got some, and when we went back to distributing the rest of the leaflets, we tried to stay in the shade. With sparse tree covering, it was next to impossible. Eileen was wretched. The pink spread from her face to her shoulders and back. I’d brought a frayed long-sleeve shirt in case it got cool at night. She put it on, but it chafed at her arms and shoulders and gave little relief.

By evening she felt even worse. I was afraid for her. The shirt came off. She was too sore to move much. Then her face started to swell. At a makeshift clinic set up for the demonstrators, we located a doctor who wrote a prescription and gave us the address of an all-night pharmacy in downtown Miami. With medication, the swelling went down and the pain subsided a little, but her whole upper body was still tender and once she got settled it was excruciating to move. It hardly mattered that rain had begun falling in sheets and we had to spend the night in the car. For Eileen, the sleeping bag wouldn’t have been any better.

Sunday morning was miserable. It was painful for Eileen to move. We sat together in the shade of a tree. I left her side only to fetch food and drink for the two of us. In the afternoon she felt a little better, and was able to walk slowly. I sold a few Party newspapers, but my heart wasn’t in it. The next morning, I drove out to a business park in the suburbs to deliver the car. I’m not sure how it smelled after we’d lived in it for the better part of four days, but I handed over the keys and got out of there before they had a chance to complain.

Though the Democratic National Convention was just starting on Monday, the communist contingent from Atlanta, including Eileen and me, needed to get back to work. We’d spent the part of four days promoting the cause; now the plan was to head home in the Party van. We left in the early evening. If each of us took a turn at the wheel we could drive straight through the night and be home before daybreak.

To keep the driver alert, someone else stayed awake to provide company. When it was Eileen’s turn, early in the morning, Irma Jean, the leader of our local Party branch, volunteered to sit up front with her. Since I had already taken my turn driving, I curled up awkwardly on the back seat and instantly fell into a deep sleep.

We’d been driving an hour or so when I felt a jolt and woke up facing backward. Through the rear windshield I saw a pair of headlights bearing down on us, flanked by yellow marker and clearance lights: a tractor trailer. It took me a second or two to realize which way I was facing—that the truck was following us, not rushing toward a head-on collision. During that brief interval, halfway between waking and sleeping, I must have gasped or called out a warning, because when I looked up to the front of the van, I could see Eileen flinch and look quickly over at Irma Jean.

I lay back in confusion, trying to work out what had just happened. In a split second the harmony of the past week seemed to have fled. For the first time since the exchange about string beans, I felt her frustration with me. Did she think I had panicked? Did she resent my distrust of her driving? Should I try to explain that I woke up disoriented and didn’t know which direction I was facing? Or would that sound defensive? Would it be better to stay silent and act as if nothing had happened?

I mulled over these choices for a few seconds. Later, I would look back on this incident, like the Kelly-green coat and the exchange about string beans, as a portent of what lay ahead for Eileen and me. At the time I was in no condition to entertain any such thought. In my dazed state the decision about whether and how to respond was too much for me. Wishing I could wind the clock back to that first tender night Eileen and I spent sightseeing, I slipped back into sleep again.