A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

For all kinds of reasons, being a radical activist was a dangerous business in the early 1970’s. Openly espousing communist revolution was more dangerous still. You would have had to be crazy not to feel fear.

For most of 1970, I probably was crazy, or at least on the borderline. Being in a constant state of rage tamped the fear I should have been feeling. Meanwhile, the response of authorities to our aggression had been mild. The college president had gone to great lengths to avoid confronting us. When we held a rally for a fired worker, the union got him a new job so he wouldn’t need us to fight for him. Despite our determination to tear down society, there had been no violent response. I had not yet been in serious danger.

In the late fall of 1970, however, a series of threats entered our lives.

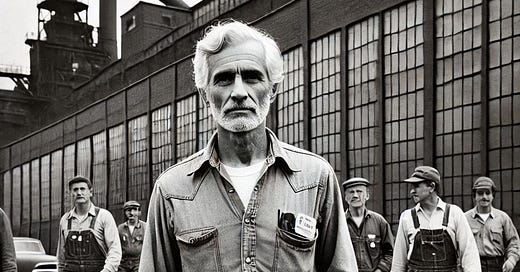

Progressive Labor (PL), the communist group I belonged to, sent us out to factories to sell newspapers at shift change. To put it mildly, the workers, especially older white workers, weren’t thrilled to encounter clusters of college students peddling newspapers denouncing racism and branding the American military as war criminals. If we kept it up, I worried we might be in for a serious beating.

PL leaders scoffed at any suggestion the workers were hostile. Party doctrine held that the working class was the revolutionary vanguard. Any complaint to the contrary was simply a projection of our middle-class fears. True, some workers might be misled by ruling class propaganda promoted for decades in schools and on television, but our job was to fight through the fog of deception. The conditions of workers’ daily lives were the best possible evidence of capitalist exploitation. If we pointed this out to them, they’d see the light and come to our side.

I didn’t entirely reject this assurance. Given enough time and patient discussion, most workers probably would agree with what we were saying. But likelihood of long-term success wasn’t much comfort when you stood in front of a manufacturing plant and a group of white workers approached demanding what in h*** you were doing there. Party leaders’ confidence didn’t help when a guy with biceps as big as your thigh asked why you weren’t in Vietnam serving your country or why you didn’t go over to Russia if you liked communism better than freedom.

Usually we sold in pairs. Having someone else by my side helped reduce my anxiety. Unfortunately there weren’t always enough of us. One morning when it was just Bruce and me, we split up to cover both sides of an access road. I was left on my own, and it felt like the incoming hostiles were all headed my way. Whenever I looked over at Bruce, he was deep in conversation with someone and paid no attention at all to what I was facing.

I should have known better than to complain, but that day I just couldn’t help myself. On the way home I asked Bruce why he was standing around talking rather than selling. Why wasn’t he paying attention to what other people around him were doing? He retorted that I was being ridiculous. He’d made some good contacts. He’d even gotten their names. Of course he was going to stand there and talk to them a few minutes. Wasn’t that what we were here for? Why did I even care anyway? Was I afraid someone would jump me? Really? When the worst anyone had ever said was “Go back to Russia”?

I couldn’t argue with Bruce. There hadn’t been any actual violence—not yet, at least. But the incident had an effect on me. It wasn’t as if I hadn’t felt physical fear before—I’d certainly felt a twinge or two when I was arrested and interrogated in the police station. But the fear I felt then lasted only a few minutes, and afterward I’d felt only exuberance. This was different—a kind of queasy feeling like a mild persistent dyspepsia, a sense of vulnerability that sheer anger and aggression couldn’t alleviate.

This vulnerability or dyspepsia or whatever it was might have died away if it hadn’t been reinforced by a bizarre incident at Rhode Island Hospital the first time I went there to sell newspapers. Emily, Bruce’s girlfriend, was with me, and we were driving my Volkswagen beetle. I parked a few blocks away so as not to attract notice of security guards. When we returned, both the driver’s-side tires were flat.

One flat tire might have meant I had run over a nail, but two made that unlikely. We were in a desolate neighborhood, two-story unkempt frame houses converted to rental apartments and a housing project in the next block. Could it have been neighborhood kids playing a prank? I’d seen no one when we arrived. There was no one around now. The only other alternative I could think of was that someone had followed us and wanted to send us a warning to stay away from the hospital.

An elderly man in a pickup pulled up behind us and asked if we needed help. He had a friend in the tire business who confirmed there were no punctures and refilled the two tires. I was sure now that someone had targeted us. Whoever it was must have identified the car that I drove and gone to the trouble of following us. That was more unsettling than the taunts at the factory gates because it was personal. Someone had gone to the trouble to find out who we were and had sent us a message.

Not long afterward, I got a call from my uncle that reinforced my suspicion. The Boston Globe had published an article about subversive groups in New England, naming me as the leader of PL in Rhode Island. He wanted to warn me before my father got wind of the story.

I was stunned by the news. Since when did a major Boston newspaper report on a tiny radical group in Rhode Island? And why did they name me and not Bruce, the actual leader? All I could think of was that the source of this story must be the same person who flattened my tires. Whoever it was knew not just who we were but also who I was.

I didn’t talk about any of this in candidates’ class, the group of neophytes being prepared for Party membership. I knew their response would be different from mine. Threats, they would argue, were a sign of success. We were getting under the skin of powerful people. Why confront injustice if you’re going to balk at the first threat to your personal safety?

I knew all that intellectually, but it wouldn’t help with the fear. The fear was real. The danger was real. To fight for justice was one thing. Everyone should do that. I wasn’t about to let the threats stop me. But to treat them as trivial, to shrug them off as an inevitable sign of success, that was something I was not going to do.

By now I was growing more and more disenchanted with candidates’ class. I kept hoping we would learn more about Party doctrine and communist history, but the leader, Caleb, kept the focus squarely on us neophytes and our shortcomings. All too often the obstacles to improvement lay in our personal lives. One by one the candidates were singled out for interrogation and criticism. I hated seeing that and dreaded the day when I, too, would be shoved under the microscope.

Even an apparently innocent comment could trigger a barrage of questions, criticism, and advice for improving oneself. Myra, a student at Northeastern University, made the mistake of mentioning a man she was dating. Somehow she got drawn into revealing that she was simultaneously dating another man and sleeping with both of them, each unbeknownst to the other. She didn’t seem in the least ashamed of this disclosure; her smirk of pleasure suggested she thought of it as an oversight rather than something wrong or deceitful.

PL, unlike other radical groups, did not condone promiscuity. I appreciated that. I was disappointed, though, that criticism from other group members focused not on Myra’s amoral lifestyle but on its detrimental effects on her basebuilding efforts. A disorderly personal life made it harder to focus on the struggle for justice. Even worse, if discovered it would make us look bad to the workers, many of whom favored a more conservative lifestyle. Apparently in their eyes promiscuity wasn’t wrong in itself but merely distracting.

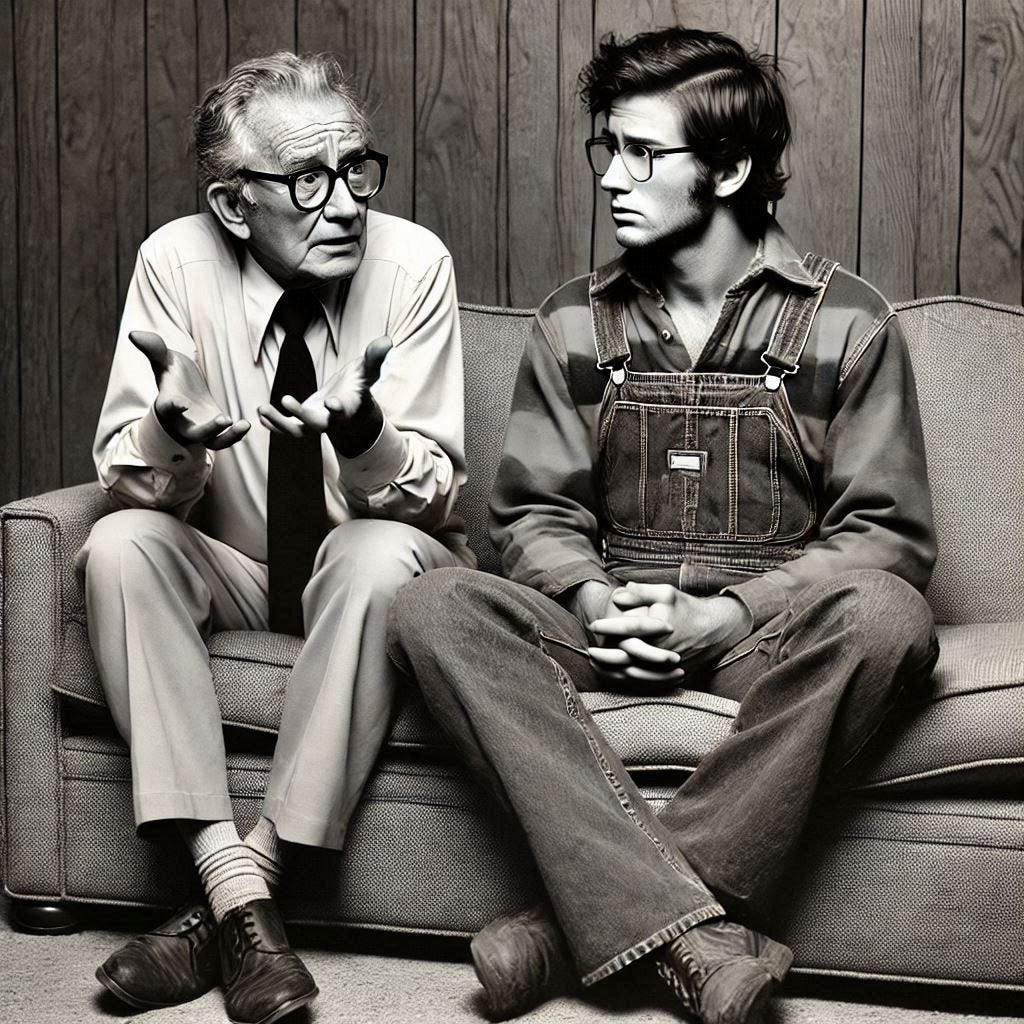

Uncomfortable as the discussion of Myra made me, it was nowhere near as distressing as the treatment of Alisdair. By 1970, Alisdair was in his mid-forties, had been on the Harvard faculty for five years, and was headed for a distinguished career in analytic philosophy. He had been a fellow-traveler of the Party for several years and was as active as any of us. In meetings, however, he spoke like a typical professor. Every statement had to be qualified. That irritated Caleb. As the class wore on he began to nag Alisdair, questioning his sincerity and commitment without any apparent reason. His stridency made me wonder if Caleb resented Alisdair’s career or was nursing an old grievance from his days as a student.

His antagonism reached a climax one evening when the subject of Alisdair’s marriage came up. Divorced in the early 1960’s, he’d since been remarried to a professor at Wellesley. Someone remarked that his wife hadn’t been seen at this or that demonstration. That opened the floodgates. Why hadn’t she come? Had Alisdair asked her to? Had he struggled with her? What was her reason for not coming?

Alisdair’s halting efforts to answer these questions embarrassed us all. I sensed the group was ready to move on to some other subject when Caleb, who had been silent until now, entered the fray. What was becoming increasingly clear, he declared, was that Alisdair never really challenged his new wife’s political views. In fact, he deferred to them. In this marriage, it was hard to see whether the fight for the rule of the working class even mattered. Did Alisdair think he could go home every night and just shut the door on class warfare? How did he expect to sustain his marriage if he used it as a shield from political struggle? Didn’t he see that he was repeating the pattern of passivity and evasion that ruined his first marriage?

It was excruciating to listen to this. What could Caleb possibly know about Alisdair’s personal life that justified comments like this? And why would he bring it up in front of the whole group instead of talking with Alisdair privately? But of course no one dared challenge him, least of all me. We were all there by invitation, because we ostensibly agreed with the line of the Party. There weren’t a lot of options available for dissenters, apart from just leaving.

For months I didn’t speak to anyone of my disenchantment with candidates’ class, but eventually I did decide to confide in Bruce’s girlfriend Emily. She too was in the class. Most nights we rode to meetings together and debriefed on the way home.

Emily was a sweet, demure Catholic girl who never found fault or showed resentment if someone criticized her. No matter how ridiculous or trivial the point they were making, she smiled patiently, agreed the suggestion was valid, and promised to try it the next chance she got.

When I brought up the Myra episode, I was very disappointed by her response. Sure, she agreed, the conversation about boyfriends was embarrassing, but you have to be honest with comrades about your relationships. Myra, she thought, was probably relieved to have shared what she told us. She’d definitely gotten good advice from the group. Didn’t I think so?

She just didn’t get what was bothering me—the bullying tone of the questions and the casual dismissal of promiscuity as a mere distraction from basebuilding.

I tried once more: Alisdair’s case.

Yet again, she didn’t see what the problem was. She agreed Caleb was blunt. He always had been. She saw how that could make people uncomfortable, but wasn’t his basic point right? In any intimate relationship you have to be crystal clear about political things. Bruce was always forthright with her. If something was important to the cause, he made sure she understood why. She was pretty sure it was the same way with Eileen and me. Didn’t I see that if both people weren’t equally committed, then one would drag down the other? Didn’t I see that made for an unhealthy relationship?

I was getting nowhere with Emily. It felt like we were living in parallel universes, witnessing the exact same events but seeing them differently. Looking back on that conversation, I can see now it was a portent of things to come—an early indication that I was moving away from my comrades. In the spring of 1971, however, I had no clue as to what lay ahead. Disappointed with Emily’s response to my misgivings, I dropped the subject and didn’t mention it again to her or to anyone else. Back in Providence, I immersed myself in radical organizing. In the Boston meetings I kept quiet, watched the drama unfold, and hoped fervently that it would end and we would emerge as fully-fledged Party members, freed of the scrutiny we’d endured over the past months.

As it turned out, that hope was misplaced. In the end, none of the survival strategies we candidates availed ourselves of did any good. Alisdair’s patient submission, Myra’s flirtatious disclosures, Emily’s sweet acquiescence, and my taciturnity all led to the same outcome. One night, as the class came to an end, Caleb announced that this would be our last meeting. None of us, he concluded, was ready for Party membership. For now we would go back to being what we had been before the class started: “friends of the Party.”

Having observed Caleb’s capricious and authoritarian behavior for several months now, I wasn’t surprised by the abrupt end of my candidacy. At some level I must have guessed what was coming. Perhaps I realized I was better off not being a member. Beating one’s breast for not selling enough newspapers did not fit my vision of myself as an activist leader.

Failure to achieve Party membership had surprisingly little effect on my political outlook. I still thought of myself as a radical activist. I still believed violent revolution would usher in a better society. I was still convinced that PL would lead the upheaval, and that through my association with them, I would have a role to play.

What that role would be, I hadn’t worked out yet, but from the vantage point of a half-century later I can see its broad outlines were already emerging. Friendship, intimacy, keeping a low profile, and staying out of the fray until I uncovered injustice demanding precipitous action—this was the pattern of life that were gradually emerging through that first year of radical activism. These elements weren’t specific to the life of an activist; they were conducive to success in nearly all spheres of human activity. My association with PL didn’t bring about any of this. It was only the backdrop.

Not being an actual member of the Party wasn’t an obstacle to this life I was trying to establish. On the contrary, being cast out by the ideologues made it easier for me to maintain critical distance and eventually to see the folly of Marxist ambitions. Slowly, lovingly, painstakingly God was guiding me, shaping my future. I didn’t respond with great alacrity to His guiding hand, but neither did I resist Him. How could I have? In those long-ago days before I came to faith, I didn’t even recognize that it was He who was troubling me during those tumultuous years when I was involved with PL and not simply my own hypersensitive conscience.