A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

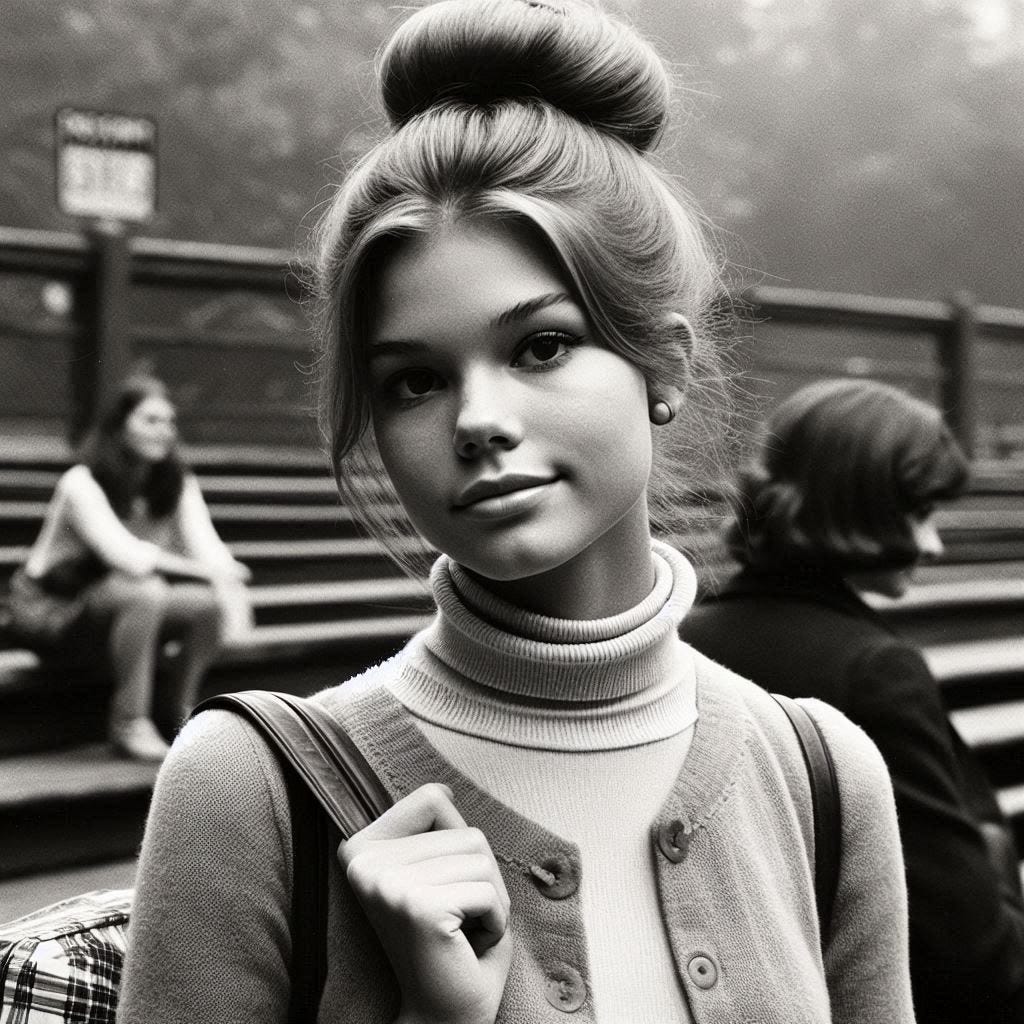

Early in the spring of 1970, soon after the failed protest at the president’s office, our leader Bruce deputized me to follow up on one of his contacts. Eileen O'Shaughnessy, a freshman art student, had been standing near me when the campus police broke up our gathering. She clung to my arm as we retreated, and afterward we exchanged a few words. Bruce saw me talking to her and asked about her reaction. I think I must have chuckled, recounting her panic at the possibility of being arrested, especially if her mother found out. It hardly seemed worthwhile trying to recruit someone so timid to a revolutionary communist movement.

Bruce disagreed.

“She comes from a working class background,” he said sharply. “She’s one of our most promising contacts. Follow up with her. Get to know her.”

I was a little resentful about that, but I knew my duty. Bruce was the regional leader, and I was hoping to advance in the movement. The last thing I wanted was to make waves

My next encounter with the young art student did little to allay my skepticism. One day, spotting a group of us in the cafeteria, she came over and sat down in the one empty seat at our table, which happened to be next to mine. I said hello and asked if there had been any repercussions at home from her having attended our demonstrations. There hadn’t been.

What to say next? I wasn’t sure, but thankfully she filled the gap.

“Can you tell me something? Bruce says they were supposed to have elections in Vietnam. Why doesn’t America make them?”

A good question, even if naively phrased. The answer took a bit of explaining. I tried to keep it short. Bruce’s explanations could be awfully long-winded.

She gazed at me for a moment. I was getting ready to elaborate when she came out with another altogether different question. When I answered that there was another and then another after that. Why didn’t Nixon end the war? What would I do if I got drafted? Why didn’t all workers join unions? Why did I start college somewhere else and then transfer here? What was so cultural about the Cultural Revolution in China? Why didn’t boys in the communist movement wear their hair long like boys in the other radical groups?

Was this some sort of test? Did she grasp what I told her? Was she even paying attention?

After she left Bruce grinned from the other end of the table. I knew what he was thinking. The art student sat down with us. She asked questions. She was winnable.

I would have liked to set him straight, but I wavered. I didn’t mind questions, even scattershot questions. Being questioned was far better than people just walking away, showing no interest. This girl’s questions might be more naïve than most, but as Bruce pointed out, in trying to win people over, you have to be patient and take differences in their background into account. I got the part about patience, but how was I supposed to get through to someone like Eileen, whose view of the world was so different from mine I had no idea where her questions were coming from?

For several weeks, the problem of this clueless young art student gnawed at me. Working in the snack bar, I would occasionally spot her sitting alone with her bag lunch at the back of the large dining area. Had she seen me as well? She gave no sign of it. If she had come up to the front where I worked at the counter, I would have said hello. It would have been easy to pick up where we left off. But she didn’t. Finally I got tired of waiting. One day I came early to the snack bar, got myself a cup of coffee, and carried it back to the table where she was sitting.

It was awkward. I could have just dived into politics, but I’d heard that people mocked us for incessantly spouting communist doctrine. So instead I asked about the bag lunches. Did she always bring lunch from home? Didn’t she ever buy anything to eat at school?

That earned me an odd look, almost a squint. I’d made her self-conscious. With a nervous laugh, she said Ma packed the lunches for her. She had no choice about them at all. Ma didn’t have money to give her to buy anything. Every day when she got home, Ma asked if she ate everything. Ma didn’t like to waste food.

That shocked me. Couldn’t she have gotten a job as a student worker? I did my best to hide my puzzlement. Her father, she explained, had worked on the railroad. He was killed in a work accident. Her tuition and books were paid for by Railroad Retirement. The problem was living expenses for Eileen weren’t. Ma had a small pension and a part-time job as a doctor’s office receptionist, but that brought in barely enough to support her and Josie, Eileen’s younger sister, let alone pay for Eileen to buy lunch every day.

I had a lot to think about at work that afternoon. I felt a little ashamed for not having taken Eileen seriously. I didn’t like to admit it, but Bruce was right. Poverty radicalized people. Eileen might be a real prospect. The problem was, if Ma kept such a tight leash on her, how could she possibly get more involved? From what she told me, if she rearranged her schedule even slightly, Ma was bound to find out. There would be trouble. Eileen didn’t want that. But if she got involved in radical politics, how could she expect to avoid it?

Eileen’s reaction to the rally for Roger gave me a new glimmer of hope. She was in the snack bar that day and saw the whole thing. When I talked to her later she told me she really liked hearing from Roger’s wife Shirley. She’d been angry when the fraternity bullies tried to drown Roger out by turning the volume on the juke box all the way up, and she wanted to cheer when Big Mike went over and pulled out the plug. What would have happened if one of the frat boys tried to plug the juke box back in? She would have liked to see Big Mike give him a thrashing. And what about Roger? She hadn’t heard any more about him. Did they give him his job back? She hoped so. He didn’t deserve to be treated like that. Why couldn’t bosses ever admit they were wrong?

This felt like progress. Pushing further, I told her about the union finding Roger another job on condition that he break ties with us.

“But why? Why not let him talk to you?”

“They don’t want to admit they’re a do-nothing union and didn’t want to fight for his job.”

“Those bums!”

A tinge of pink crept into her pale cheeks. You could see the schoolgirl in her when she got angry. Time to press harder about coming to meetings. How were we ever going to fight the bosses and corrupt union officials if people didn’t participate? Why couldn’t she make up some sort of excuse for Ma? Couldn’t she say she had to work late in studio? Or study with a friend?

She narrowed her eyes, thinking about this.

“If I say I’m studying with a friend, she’ll want to know which friend.”

Which friend. It was hard to believe she let her mother control her like that. I wasn’t about to give up, though. Not with Jim pestering me to keep trying.

For a long time I didn’t talk to her about me. I was very guarded in those days, not just with her but with everyone.

I’d gone to private schools all my life and spent two years at an Ivy League college. Fellow-activists knew very little about that phase of my life, and I didn’t want to enlighten them. If I had, I’m not sure I would have even known what to say.

A year after leaving the Ivy league school, I still could have gone back there, but I just couldn’t see myself doing that. I told myself I was dedicating my life to destroying the privilege I’d grown up with. I can see now how preposterous that plan was. The Gods of revolution are fickle. Soon enough they would turn against me, but elite education is its own sort of false God. I knew in my heart it provided no sanctuary. However uncomfortable I felt in the tumultuous, angry life I’d built for myself in the spring of 1970, I felt no inclination at all to go back where I came from.

There was no way I could have explained all this to the people around me at Rhode Island College, but as time passed and I felt more comfortable, I was able to open up and share a little of myself with a few people. The first serious subject I talked about was the odd encounter when I went for my draft physical. Being summoned for an exam of this type was a common experience for young men, but the unique spin on mine—being given a draft deferment I hadn’t asked for, without medical evidence—still perplexed and amazed me.

I had no particular purpose in mind in mentioning the draft physical to Eileen, other than to pass the time before telling her about yet another meeting Bruce wanted people to come to. I was surprised how she perked up when I told her about being prodded and poked by the doctors and medics. I hadn’t expected this to be of any interest, but suddenly there were questions flying this way and that. Were they rough? Were they abusive? Were there other young men going through this or was it just me on my own?

When I finally got around to the mysterious man in the back office and the unasked-for deferment, she just stared at me for a few seconds before gasping,

“They know who you are!”

I nodded, not wanting to make a big deal of it.

“They’re watching you.”

“They must be.”

“Filthy rats!”

Her eyes glistened. Indignation transformed her. It was hard to believe she was the same girl that let her mother browbeat her about studying with friends or working late in studio. I was beginning to realize there was more to her than that, but where did it come from? No sooner had I wondered that than I got an answer. Pa, she said, was a strong union man. He was always talking about the bums who got rich off his work and the filthy rats who squealed on coworkers for taking one break too many.

This felt like progress. I would have liked to hear more, but I was already late for work, so I broke it off, promising we would talk later. Later, though, didn’t come as soon as I had hoped. The next few days I didn’t see her in the snack bar. Was she avoiding me? Had I said something wrong? Was she self-conscious about Pa?

Just as I was beginning to despair of picking up where we left off, I spotted her when my shift ended, standing by the door that led out of the snack bar. I was on my way to a late afternoon class, so I had no time to talk, but it turned out she had a class in the same building. We walked over together.

The days were longer now. It was still warm outside. I waited for her to say something more about my draft situation or about Pa, but she seemed preoccupied. Finally, as we were about to part in the atrium of the classroom building, I asked what was the matter.

“Ma’s sick. She’s taking these pills. She can’t drive.”

Ma again. Could we please, just this once, talk about something else? As it turned out, though, this wasn’t about Ma. It was about Ma’s car. Ma had let her drive to school on her own. She’d parked over by the dorm where I was living then.

“We could walk back together after class.”

To the dorm? I hadn’t planned on returning there right after class, but I could if I needed to. She still seemed to have something on her mind that she wasn’t telling me. Maybe between here and the dorm parking lot she’d work up the nerve to come out with it.

Class took forever. When it was finally over, I looked for her and there she was, standing by the door. It was cooler now. We walked slowly toward the dorms, still not speaking much. If she really had something to say to me, why was it taking so long?

When we got to her car she put her bookbag in the front seat on the passenger side and turned as if to say goodbye, but didn’t. It was very awkward. For several seconds she just stood there with her face tilted toward mine. I remembered how sweet she looked when she called the weird man in the office a filthy rat. I just couldn’t help myself. I bent down and kissed her.

To my astonishment she put her arms around my neck and kissed me back hard.

The very next day, when I saw her in the snack bar, she said she’d told her mother she was going to have to spend more time in school, studying and working in studio. I couldn’t help chuckling. Just like that. After all those weeks, the problem of Ma simply vanished.

Almost at once we began to find more ways to spend time together. Without me even asking, she joined the movement. From that day on, there wasn’t a meeting she wasn’t at. Bruce didn’t say he’d told me so, but I could see that he was pleased to have her there.

For the next few years, she was such a blessing, I know God must have sent her to me, using Bruce to make sure I didn’t ignore her and let His gift slip through my fingers. It’s amazing to realize that He used one atheist to bless another, but of course He would have known I wouldn’t be that my whole life.

Painful times lay ahead for Eileen and me, but for that first year, at least, we were at peace together and always in each other’s company. In the storm of radical protest, she was my refuge and I hers. The tenderness of those years was God’s gift to us, until by our sin we spoiled it.