A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

In the spring of 1971, at age 21, I was deeply involved in the communist movement in Rhode Island, where I was then going to college. Bruce, the local leader in Providence, invited my girlfriend Eileen and me to join a community protest in Roxbury, the black section of Boston. Ordinarily we wouldn’t have traveled to a demonstration an hour away, but this one sounded intriguing: a protest at a local grocery store that allegedly raised prices on the first of the month, the day welfare checks were issued.

As an added inducement, Bruce promised to find somewhere for Eileen and me to spend the night afterward. Eileen, who was 19, was living at home with many restrictions. We were thrilled at the chance to spend a whole weekend together—no questions and no curfew.

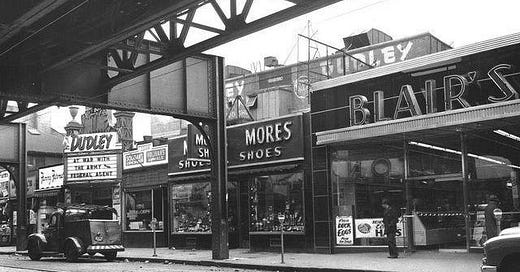

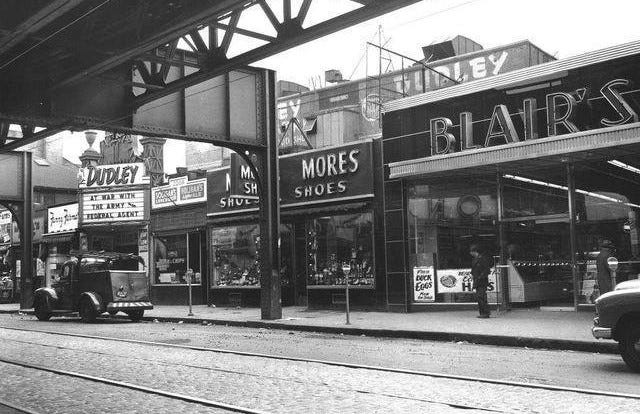

The target of our demonstration was Blair’s Market, a small grocery store near Dudley Station in Roxbury, the heart of inner-city Boston. The event was billed as a neighborhood protest led by working-class residents. Because our organization, the Progressive Labor Party (PL), was a lot stronger in Boston than where Eileen and I lived, we expected to see a large local turnout and were dismayed to find fewer than a dozen people at the gathering point.

The little group huddled in a parking lot near the store consisted entirely of college students and ex-students. After waiting in vain several minutes for stragglers, we stamped through midmorning slush to a narrow storefront protected by steel mesh shutters. Despite the hour, there weren’t many shoppers up and about yet. Huddled together, our little protest group felt conspicuous. It didn’t help that we were the only white people in sight.

The interior of the store was cramped and dimly lit, and the handful of protestors made it feel crowded. We walked single file down narrow aisles between bins of tired-looking produce and dusty shelves stacked with cans to the back of the store, where we crowded around a glass-fronted case displaying brown-tinged beef and dull-looking chicken parts.

From behind the meat display, a lone employee asked wearily what we wanted. Several of the protestors unrolled signs, and a stocky young protestor in a ski hat announced we were the Roxbury Worker-Student Alliance and launched into a list of complaints.

The store employee tried to say something back, but was drowned out by a chorus of shouts from the demonstrators: “Fresh produce!” “Decent meat.” “Lower prices.” “Stop cheating your customers.” Eileen's eyes met mine, and I could feel her apprehension. What were we accomplishing here, and how were we going to get out if there was trouble?

A young African-American man spoke up from behind us, over by the vegetable bins. Pitiful, he exclaimed, holding up a head of wilted lettuce. He worked in a hospital kitchen. He knew inedible food when he saw it. What we saw here would never have been fed to the hospital patients.

This, I realized, must be the worker in “Roxbury Worker-Student Alliance.” I’d assumed there would be a lot more than just one, but one was better than none. At least one local person had a bone to pick with this store, so we weren’t here under false pretenses.

Even so, it was hard to see what we were going to accomplish. The store employee, standing there in his stained apron, just stared at us. He didn’t have any answers. Assuming the owner didn’t show up, what was our end-game?

No sooner had I posed this question than an answer presented itself. The front door of the store banged open and half a dozen policemen barged in brandishing nightsticks. How they knew we were there, I had no idea. The store owner couldn’t have called them. He’d been standing there staring at us the whole time.

There was no standoff or warning, as there had been when a group of us students demonstrated at our college president’s office. The six cops closed in on us quickly, cursing and shoving us toward a rear exit that opened onto a stairway. A couple of the bolder comrades turned to face them and tried to resist, but with the nightsticks pressing against them at chest level, they couldn’t get leverage. Packed into the small space at the back of the store, we’d been cornered. Our only line of retreat lay through that three-foot-wide doorway that led to cement steps. I could see no conceivable point in resisting.

In the melee I got separated from Eileen. Looking around in panic, I spotted her near the doorway. Close to safety. That was good. But then one of the cops, who was standing just a little behind her, raised his nightstick over his head. Someone yelled. Eileen lost her footing. One of her arms flailed. I lost sight of her. All I could think of was that narrow, dimly lit staircase and cement steps leading down to who knew where.

I struggled toward the stairs, dreading what I’d find at the bottom. The comrades, inexplicably, were still trying to fight back. I plunged through a jungle of arms and shoulders, fists and nightsticks. After what felt like many minutes of pushing, shoving, and cursing, but was probably only thirty seconds or so, the doorway yawned in front of me and I clattered down the steep steps as fast as my feet would take me.

When I reached the bottom, there she was, spreadeagled on the gravel. A couple of our comrades lifted her up by her arms and half-led, half-carried her to the back of the parking lot.

I rushed over and put my arms around her. She was trembling. One of her shoes was missing. She cradled her arm against her. She’d twisted her wrist in the fall. Apart from a few tears, her face was okay, and as far as I could tell there was no other injury. Even so, our weekend getaway had turned into disaster.

Once she got over the initial shock and stopped trembling, the first thing she wanted to talk about wasn’t the cops or falling downstairs. It was that missing shoe. What was she going to tell Ma? She was supposed to be visiting a sick friend in the country. As for the wrist, she hardly bothered about it at all. Whatever was wrong, Ma wouldn’t wouldn’t be able to see, would she?

Thankfully a solicitous comrade drove us to the city hospital emergency room, where the wrist was x-rayed and bandaged. To my immense relief it wasn’t broken. Exposing myself to physical danger was bad enough, but exposing Eileen to it filled me with horror. At the doctor’s assurance the wrist would be fine in a few days, I felt the tension drain out of me. We’d had an incredibly narrow escape. Both of us were wrung out and exhausted. Though we would never have said this out loud, I think we both knew we had a lot to be thankful for that night. How shocked we would have been if someone asked us, thankful to whom?

We’d been invited to spend the night with another couple who’d been in the demonstration. On the way over to their apartment Eileen fretted about Ma, but when we arrived, the convivial atmosphere lightened our mood. The woman found a pair of old sneakers for Eileen to wear home. Another couple arrived, and we celebrated the great proletarian struggle with a couple of enormous pizzas and a flood of cheap beer. It felt good to be with our comrades. We'd confronted the bosses in Roxbury, the heart of capitalist exploitation and workers’ poverty. We'd stood up to police violence. We’d done our part to build a mass working-class movement to destroy capitalism. In the exuberance of the moment, no one exhibited the slightest skepticism, and not a single one of us mentioned what we all knew to be true: that all but one of the protestors that morning were middle-class students.

In retrospect, it’s understandable that no one was thinking too clearly that night. The six of us were just glad to have gotten out of that store without jail time or serious injury. Later, however, PL leadership rewrote the story in incredibly grandiose terms. The “great victory of the workers” was featured on the first page of PL’s national newspaper. No mention of how few protestors showed up on the scene or that we were thrown summarily down a flight of cement steps within minutes of starting our protest.

A year or so later, The Ballad of Racist Blair’s, composed for a long-playing record produced by the Party, reframed the incident in even more colorful terms:

Well the people fought back when the cops attacked;

Black women took the lead!

And a traffic cop ended up sitting in the deep freeze

Next to the milk and cheese.

Line 1 is true, if a bit optimistic: punching cops wielding nightsticks had pathetically little effect. Line 2 was false: there were no black women present, however much PL might have wished that there had been. Line 3 is also false: no traffic cop sat down anywhere, let alone in the deep freeze. They were too busy in front of that meat counter, shoving us out the rear exit. Line 4 sacrifices credibility for a clever rhyme. Milk and cheese would have been stored in a walk-in cooler, not a deep freeze.

Despite these distortions, or maybe even because of them, I treasured The Ballad of Racist Blair’s in my heart. Years later, when my children were young, I used to sing it to them, a humorous reference to the long-ago days when their now-conservative Dad was a communist. For all its ideological bias, the tune had its own authenticity, recalling a simpler time when those swept up in this great wave of anger knew the answers to all the world’s problems and resolved to remake society in a torrent of violence. It didn’t occur to me till much later that the real news in the “racist Blair’s” incident had nothing to do with that glorious but fictitious uprising, but instead that Eileen was unharmed by her fall down those cement steps. At the time I put that down to sheer luck, but looking back now I see so many other instances in which terrible things might have happened to us but didn’t, I know it wasn’t just happenstance that those cement steps didn’t do any serious damage.

After a night’s sleep, Eileen seemed refreshed, and we set out for Rhode Island with a new sense of optimism about the communist cause and our role in it. I’d been afraid she might take me to task for suggesting we go to the protest, but she didn’t. We spent most of the hour long drive brainstorming what to say about the sprained wrist and lost shoe. Eileen decided she could explain the wrist simply by saying she walked through her sick friend’s house swinging her arms and hit one on a door jamb. The problem of the shoes was more difficult. Finally she decided simply to tell Ma she took them off last night, and when she awoke one was missing. If Ma challenged her, she’d just agree she’d been stupid and careless. Who would invent a story like that?

I felt queasy dropping her off that night. Deceiving Ma about where she slept Saturday night was a risk, but the other excuses were so farfetched It was difficult to imagine Ma taking them seriously. Eileen, though, was determined to see the plan through. When I saw her in school the next day, she greeted me with a huge grin. Smashing her wrist on the door jamb had turned out to be totally believable. In Ma’s eyes, she was that clumsy. And the shoes? She pointed gleefully to the old tennis shoes she was still wearing. Ma had warned she’d better get used to them. She was going to be wearing those a long time before Ma would be able to come up with enough money for new ones.

The Blair’s Market protest was a milestone in my life as a radical organizer. It was the first time I’d been exposed to actual violence rather than just threats and warnings. We’d gotten plenty of those when we sold newspapers at factory gates, but none of the workers who expressed their hatred with such vitriol ever did anything physical. For the first time, I saw how narrow the line was between words and bodily harm. At Blair’s Market, Eileen and I had been incredibly lucky. The next time we might not be. It was the most obvious clue to date that this great adventure of ours might not lead to the glorious outcome portrayed so vividly in Party literature. I didn’t dwell on that thought, but it lurked somewhere at the back of my mind, and I suspect it took the edge off the aggression that had driven me during the past year.

The effect on Eileen was quite different. Paradoxically, being caught up in a violent confrontation and surviving it gave her a huge boost in confidence. Not only had she emerged unscathed from that plunge down the stairs, but she had completely avoided repercussions from Ma. With new confidence, though, came a surge of exasperation about Ma’s restrictions. Later that spring, she made an astounding proposal. What if we moved out of town that summer and lived together? We could go to Boston, get jobs, and rent an apartment. How would Ma even know where we were living?

I could scarcely believe it. Was this the same girl who less than a year ago stubbornly refused to come to an hour-long meeting for fear of Ma’s questions afterward? I agreed at once and we began planning.

When Bruce, the local Party leader, heard that we wanted to leave town for the summer, he offered a different suggestion. PL was planning a national Summer Project to broaden its reach. Organizers from large chapters like New England were traveling to Houston, Atlanta, and Washington DC, where fledgling groups were struggling to make headway. Atlanta in particular was in need of more manpower. Why not join the group headed there?

Eileen and I talked it over. Bruce’s suggestion appealed to me. I’d never lived in the South before. Spending the summer in Boston, where I’d lived when I first went to college, would be basically just treading water. We’d have to work long hours in low-paid jobs just to pay rent. In Atlanta rents were cheaper. If necessary we could share quarters with other volunteers. By joining the PL Summer Project, we would be helping strengthen the movement.

For Eileen, though, moving down South had altogether different implications. If we were in Boston we could drive home if Ma needed her. Not from Atlanta. Apart from Josie, Eileen’s younger sister, Ma would have no one.

Over the course of several days, we talked for hours about these two possibilities. I could see Eileen’s point. Ma was poor. Ma was isolated. She didn’t have family or a whole lot of friends. Still, I wasn’t convinced Ma actually did need Eileen in the way Eileen thought she did. Eileen wasn’t working. She didn’t bring money into the household. Wouldn’t she eventually leave anyway when she finished school, got a job, and got married? If she was going to go someday, why not now?

I don’t know how much pressure I put on Eileen to do what I wanted. I tried to keep the conversation low-key, but I’m sure it was obvious to her that giving up the chance to go to Atlanta for Ma’s sake didn’t make sense to me. Undoubtedly the difference in age and level of self-confidence came into play. At 22, having lived on my own several years, I knew what I wanted. At 20, still living at home, Eileen wasn’t so sure. Small wonder that she eventually came around to my way of thinking.

So it was that in early June the two of us boarded a bus bound for Logan Airport in Boston. It was a solemn departure. Ma, anxious and grim-faced, made Eileen promise to write to her from Atlanta because she couldn’t afford to be calling on the telephone all that way and neither could we. In silence we watched her retreat to her parked car. Eileen’s bare arm pressed against mine. I felt her stillness. She was leaving behind a lot more than Ma’s rules and restrictions.

Not until the bus pulled out of the station did our mood start to lighten. Whatever summer in Atlanta held in store for us, we were sure we could deal with it. We did not know what enormous changes lay ahead of us. Looking back now, I marvel at the innocent optimism of that young couple, setting off to they knew not where with passion and confidence that there was no obstacle they couldn’t surmount. They did not pause to consider the sequence of providential events that led to that juncture. Blair’s Market; Eileen’s bold excuses; Ma’s credulity; Eileen’s determination to leave home; the growing threat of violence from a shadowy adversary; and the opportunity to move to Atlanta. Together they pointed toward a momentous change that lay in the future: sin, chastisement, forgiveness, reconciliation, and a foretaste of the Lord’s Kingdom.

Those two young people couldn’t have known that.

But He did.