A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

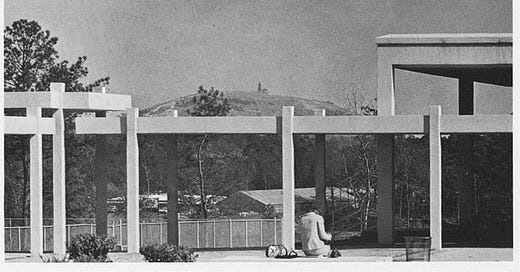

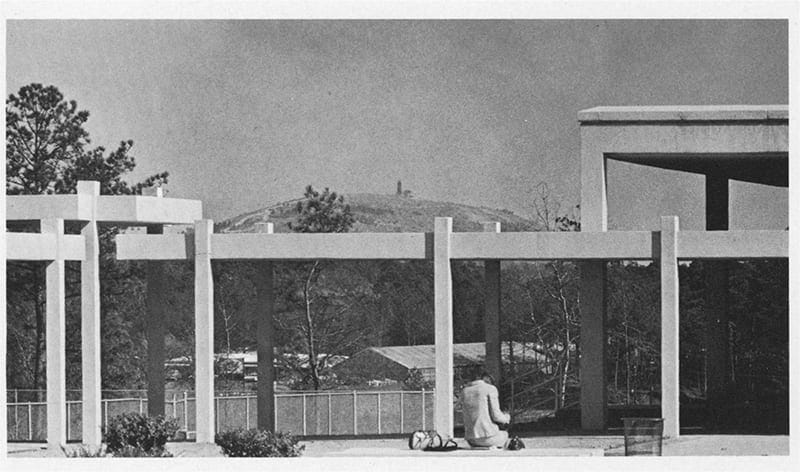

The local leaders of the Progressive Labor Party (PL), the communist group my girlfriend Eileen and I volunteered with in Atlanta in the summer of 1971, weren’t satisfied with the progress of the group from New England. Early-morning excursions to factory gates didn’t yield the harvest of contacts they’d hoped for, and there was little for us to do during the rest of the day. To keep us busy, they decided we should take courses at a local junior college and try to recruit fellow students. Eileen and I and several others enrolled in DeKalb Junior College, 10 miles from the city

Spending the hottest part of the day on a college campus was a welcome relief from our sweltering little apartment, not to mention the tense encounters at factory gates. In the clean, modern buildings, I was cool for the first time since we arrived in Atlanta. It felt good to be around other students again. No puzzled looks or suspicious stares followed us as they did in stores and restaurants downtown.

We soon found, however, that Dekalb Junior College was not as welcoming as it appeared. Unlike in colleges up north, selling newspapers was forbidden. So was passing out flyers. In our very first week we got several stern warnings, and after that campus police seemed to be everywhere. The apparently peaceful campus was beginning to feel like a totalitarian state.

To avoid confrontation, we began sneaking in newspapers folded inside a notebook. We would sit down with a prospective recruit in the cafeteria or student lounge, strike up a conversation, and then casually show them the newspaper. It was a hard way to spread our message, and we made very few contacts.

After several days of this cat-and-mouse game, it was decided we should go on the offensive. We wrote up a leaflet denouncing the college’s “police state” tactics and their encroachment on our freedom of speech.

Getting these leaflets into the hands of the students was no easy task. The best strategy, we decided, was to leave a few here and there where students would be likely to see them before the police did. Wherever we went we scouted out drop sites. Bathrooms were prime targets. So were empty classrooms and library tables and carrels. At most they remained where we left them an hour or two before the police or the cleaning crew found and discarded them. How many students found and actually read them, we had no way of knowing.

Of course leaflets and newspapers weren’t the only way to reach fellow students. Going to class every day gave us each an audience that campus police couldn’t monitor. I chose my course with care. Microeconomics, I thought, would offer an unparalleled platform for a Marxist to make his views known.

The atmosphere in the class wasn’t exactly conducive to debate or discussion. The other students were so quiet, it was as if they’d entered into a compact not to react to anything Dr. Bliss, the elderly instructor, said or wrote on the board. I knew, however, I couldn’t just sit there indefinitely and say nothing. Midway through a lecture on the inputs of production, my hand shot up and I could everyone’s eyes on my back.

Dr. Bliss paused. I guessed nothing like this had happened in one of his classes in a long time. Then, to my puzzlement, he put down his notes and asked with elaborate courtesy how he could help me. This was utterly unlike the response I was expecting, but I plunged ahead anyway. Why, I demanded, should “entrepreneurial talent” be included as one of the inputs of production, along with land, labor, and capital? What did it actually contribute to production, apart from extracting profits for capitalists by cheating workers out of the wealth they created?

Another long pause. It felt like the students behind me were holding their breath. Then, to my amazement, Professor Bliss smiled.

“Ah, Mr. Howell”—how did he know my name, when this was the first time I’d spoken?—“Mr. Howell has made a most interesting point. Let’s think about what he just said.” Over the next several minutes, he proceeded to question me, gently probing the implications of what I had said in a way that helped clarify how the traditional view of production differed from the Marxist view I was defending. I remember thinking not only that he’d given a fair summary of our differences, but also that our exchange had actually amused him.

Mr. Howell objected to a great deal during the remaining weeks of that summer term. Whenever I raised my hand, Prof. Bliss called on me promptly. His response was always thoughtful, polite, and encouraging. Sometimes he took me by surprise, calling on me when my hand wasn’t raised. Did I agree with some point he had just made? Did I have a different point of view that should be considered? I would hastily cast my mind back over what he’d been saying and try to come up with some kind of objection.

What irony! I’d set out to challenge him, but now it was he who was challenging me. I’d been used to a caustic reaction from professors I criticized. Here was a man who actually enjoyed our repartee. How little of that he must have experienced in the decades he had taught at Dekalb Junior College! It was hard to imagine local students like those in class with me now debating him as I did. What must it be like to drone on and on through a lifetime of indifferent, blank faces, never to be asked a real question, let alone encounter a bona fide challenge? His eagerness to elicit an argument, even when I was half asleep and had no inclination to offer one, was a sad spectacle. It was hard not to feel sorry for him. It was hard to maintain the seething indignation needed for a proper defense of the cause.

Despite ample opportunities to preach socialism in class, I wasn’t optimistic about recruiting those silent students in microeconomics. The entire six weeks I managed to sell just one newspaper—to Amos, the lone black student, who I assumed would be more open to revolutionary ideas than our whiter-than-white peers.

I wasn’t sure at first how to approach him. One day, arriving a few minutes early, I found an empty seat next to his. As he gathered up his books after class, I asked what he thought of economics. Pretty dry, he replied. A lot to memorize.

“But not for you, man,” he added, chuckling. “I never see you write anything down.”

I laughed. In those days it never occurred to me to take notes. I didn’t care what grade I got in the class, and I was too busy looking for a chance to argue with the professor.

Neither of us had a class the next period. Amos was headed toward the library, so I walked with him. We found a free table to sit at and I showed him the newspaper. He took a long look at the front page, which pretty much laid out the whole Party line—exploitation, smashing capitalism, the leadership of the Party, everything.

“Is this for real?”

He looked up at me with a quizzical grin. What in the world was I doing carrying around something like this? Was I looking to get thrown out of school? He couldn’t get over it. A communist? At DeKalb Junior College?

His incredulity caught me off guard. White Southerners’ hostility made perfect sense—we were here to tear down their precious traditions. It never occurred to me that blacks might think we were crazy for trying. Still, Amos was so good-natured I couldn’t help grinning. Maybe I had a shot at winning him over.

I pressed harder, throwing out a few examples of the evils of capitalism. He nodded thoughtfully. He didn’t deny that the people in charge were corrupt, racist, and greedy, or that they were trying to squeeze every drop of sweat they could out of the workers and reduce them to poverty.

I asked if he would consider coming to one of our meetings. This time he laughed outright. Get tied in with communists? Not a chance. He had to be careful. He had a wife to support back in his hometown south of Atlanta. He had a good job on the night shift at the GM assembly plant. Great benefits. The company was paying for him to go to school to get a degree.

Tuition benefits! That didn’t add up. Why would a company pay tuition for assembly line workers? What degree could he possibly be working toward?

He didn’t want to say at first, but at last I got it out of him. Business. He was going for a business degree. How else was he going to make it to management?

Now I was really shocked. Make it to management—for real? He was an assembly line worker. He’d just admitted the bosses were corrupt, racist, and greedy. So he wanted to be one of the ones squeezing the lifeblood out of the workers?

You would have thought my logic was airtight, but Amos just listened and smiled and shook his head. Getting into management wasn’t about hurting anyone. It was about lifting up him and his family. Pretty soon he and his wife would want to have kids. How was he supposed to support them, buy food and school clothes, pay doctor bills? As an hourly worker what chance would he have of buying a home so he would have somewhere to raise them?

I had no idea what to say to him. My first impulse was to tell him he was buying into the ruling-class lie that anyone can get ahead in the world if they just work for it. But was this really a lie if you looked at it from his point of view? Considering his particular situation, wouldn’t he be better off with a white-collar position than as an assembly line worker? Party stalwarts like Peter and Irma Jean might say that he should stay poor, fight, and plan for the workers’ uprising, but I couldn’t bring myself to tell him that now.

Amos and I chatted several more times that summer. Back in the apartment, I reported the contact to Peter, who passed the word along to the local Party contingent. Everyone was impressed. They’d sent me to college and I’d recruited an auto worker! Each new report of a follow-up conversation brought more kudos. Thankfully no one found out about his plan to “make it to management” or how little effort I’d made to talk him out of it.

Amos never did come to our meetings, but eventually I persuaded him to buy one of the newspapers. He folded it meticulously and slid it into the pocket of the binder he carried his notes in so no one would see. After our first exchange, I didn’t bring up the business degree. From his point of view, it was he who had made the practical choice. I was the one looking at the world through rose-colored glasses, traveling all the way down from New England to proclaim what no one in Atlanta wanted to hear. I didn’t agree with him about that, but in hindsight I realize it was a step forward to discover someone saw me that way.

Amos’s influence on me didn’t stop at summer’s end. After our last economics class he gave me his phone number, saying if I wanted to get together I should give him a call. With only a few weeks before our summer of volunteer organizing came to an end, I assumed we’d all be heading back north soon and I doubted I’d ever see him again. To avoid giving offense, though, I carefully folded the slip of paper he gave me and slid it into my wallet.

After Eileen and I decided to stay on in Atlanta, I found the number and called him. He introduced us to several hometown friends, who in due course became our friends. Many a night we would sit with them, listening to the stories they carried pent up inside them and sharing in the relief they felt in finding an audience. Looking back on that summer, I realize now that God must have orchestrated the meeting with Amos, who embraced the system I had set out to destroy, and with the two men who were eager to share their burdens with a young white college student from the North. Through the three of them I learned a lot about what the world was like that I couldn’t have learned elsewhere. In the process I discovered a side of myself that had nothing to do with violent upheaval.