A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

In August of 1972, when my girlfriend and Eileen and I set up housekeeping in Atlanta, we explained our plan differently depending on who we were talking to. Our official reason, the version of the story we shared with our close friends, was that we had moved south to organize for a communist uprising. In private, we also recognized this move was our best chance to live together, free of the restrictions of Eileen’s widowed mother back in Rhode Island, and far from my father’s outrage that I’d traded an Ivy League education for a life of radical activism.

For our parents, of course, we had an entirely different story. This was the classic career move. We were going to be teachers. Georgia State University, located in the heart of downtown Atlanta, offered an excellent teacher preparation program, far better than the small college in Providence we attended the previous spring.

The outcome of our move to Atlanta proved to be quite different from what we told ourselves, our friends, or our families. We drifted away from radical activism. Setting up housekeeping together did not strengthen our loving relationship, as we had expected. Our career plans led to a dead end. Eileen switched majors, then dropped out of college. I completed my degree but taught only a few years. Looking back now as a believer, I see that God did not endorse our intentions, but He did bless us in other ways. For me, at least the effort to establish ourselves in Atlanta bore the strange, sad fruit of perplexity and a glimpse of my own limitations.

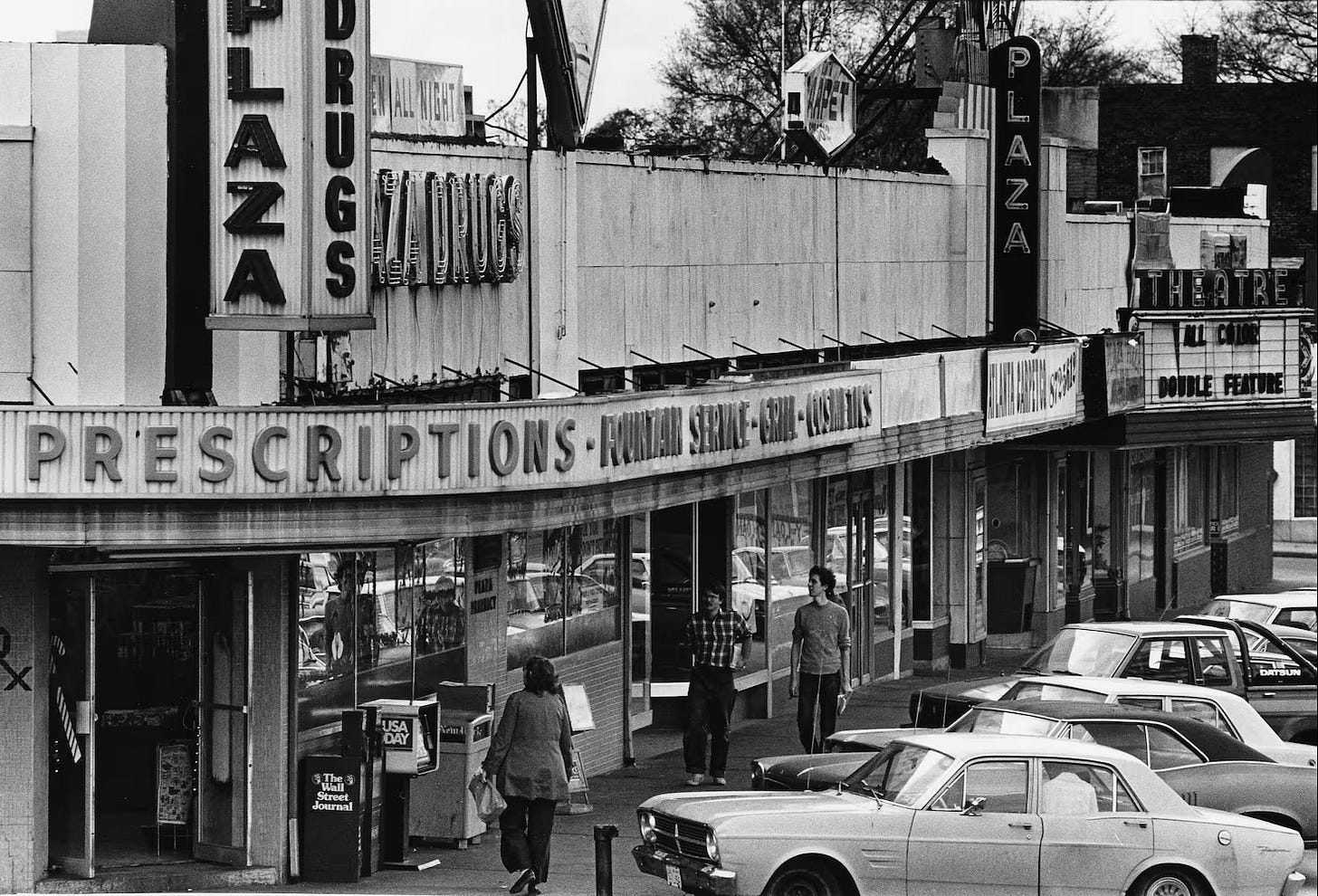

When Eileen and I decided to stay on in Atlanta, the first person I told was my friend Jim. His outpouring of enthusiasm surprised me. He spent an entire day helping us hunt for apartments. Jim had grown up in foster homes, and he had a keen eye for the seamier sights in our new neighborhood. At Dupree’s, the gay bar on Ponce de Leon, his friend’s promiscuous mother dropped off her alcoholic husband for the night so she could cavort with a new lover. The lunch counter at Plaza Pharmacy, where young men once took their dates for a sandwich and milkshake after a movie, was now the afternoon haunt of prostitutes. Nothing would do but that we grab coffee there and try to pick out who was for sale. With the help of Jim’s broad shoulders and a friend’s van, we furnished our apartment for a pittance from lawn sales, rounding out the new household with a couch and chairs from the waiting room of a local dentist who died.

Once we were settled, Jim was a frequent guest. He rented a room in a rooming house barely a half mile from us, and would often stop in after work. Having met Eileen only briefly during the summer, he made a special effort to converse with her, inquiring about her schoolwork and asking regularly after her mother and younger sister. He approved heartily when we acquired a kitten. Many an hour he sat stroking it, catching up on our progress in school and sharing his views on Atlanta, the world, and his foreman at work. I suspect that cat of ours got more love and attention from Jim, who had had little of it in his own life, than from either Eileen or me or the couple we eventually gave him to.

On the weekends, when the weather was good, the three of us would go for a walk in Piedmont Park and marvel at the hippies and other odd characters who loitered there. For a lark I bought a basketball. When we found a court free, we would play 2 on 1, Jim and Eileen against me. I once frustrated them so much they resorted to rushing me from opposite sides. Still dribbling, I stepped back and they collided. Neither was hurt, but Jim couldn’t stop laughing, and many a night afterward he would remind us of that hilarious afternoon when he barreled full tilt into a woman who wasn’t even his girlfriend. We filled a hole in his life, and he in ours. Thanks to his friendship, Eileen and I gradually began to feel at home in Atlanta. Even though we were 1,000 miles from where we grew up, people who grinned at our accents no longer made us feel like outsiders.

In early September, when we were established in our new home, Eileen reached out to Yvonne, a teenaged girl she’d met that summer on a recruiting trip to Grady Hospital. That fall they talked by phone at least weekly about the trials and frustrations of Yvonne’s life—an aunt getting sick, a delayed bus, a boss’s demands. From the very beginning, the friendship had puzzled me. It seemed always to be Eileen who took the initiative. When they talked on the phone, it was always Yvonne’s problems they talked about. As far as I could make out, Yvonne never asked about Eileen. I could tell from Eileen’s excitement when they talked how important this friendship was to her. What I could not see was why.

Once in a great while, when no crisis loomed in Yvonne’s big multigenerational family, she would agree to have Eileen to drive over and visit. How I dreaded those nights! It was a long trip through destitute neighborhoods and dilapidated industrial areas. Eileen was a nervous and tentative driver, and she would come home as late as 10 or 11 o'clock. Watching the minutes tick by, I could feel my anxiety ratchet up. The tension I felt must have shown, because I recall her complaining that she was perfectly capable of driving across town at night. What was the matter, didn’t I think she could drive to see her friends the way I drove to see mine?

Eileen campaigned for months to get Yvonne over to our apartment for dinner. Several dates were set, only to have Yvonne call off because of some family emergency. This happened often enough that it was hard not to suspect that Yvonne made up these excuses on the spur of the moment. After several false starts, however, the plan finally came to fruition.

I knew this was going to be an ordeal, but I also knew Eileen had her heart set on having Yvonne as her close friend, so I tried my best to make the night a success. While Eileen drove over to fetch Yvonne, a round trip of over an hour, I stayed home and fixed dinner. When they arrived at our apartment, Yvonne barely greeted me. She showed no interest in Eileen and me, the apartment, or our life together. She barely acknowledged the meal I’d prepared. We spent most of the evening talking about the details of her daily life: inconveniences, frustrations, and worries about work. The conversation was so one-sided it was hard to sit still and look interested and be a good host. It was hard to watch Eileen murmuring in sympathy and coaxing out every last painful detail.

Not wanting just to sit there looking from one to the other, I searched for a way into the conversation. When Yvonne mentioned her cousin was in a wheelchair, I asked about him. Cousin John was the son of Yvonne’s mother’s older sister, whom she referred to as “my Auntie.” He had been in a car accident in his teens. The insurance company never paid what they owed for his injuries. Now in his early forties, Cousin John was on disability, which didn’t come near covering what it cost him to live. Unable to afford a place of his own, he lived in the house with Yvonne. My Auntie lived there too and took care of him. The problem was that she wasn’t doing all that well. She had emphysema. Who would care for Cousin John after Auntie passed on?

A sad story for sure. A huge weight on the shoulders of a girl in her teens. But I still couldn’t understand why Eileen was so wrapped up in Yvonne. The way she drank in those stories of woe hinted at a thirst I’d never seen back in Rhode Island, before she left home and before we started living together.

Several more months passed after that difficult evening before I got a glimmer of insight. I was lying on the bed reading a book for one of my courses. Eileen, who had been on the phone, came in and said gravely that Yvonne’s aunt had died and she had promised we would go to the funeral.

I was glad she said “we.” I knew she sensed my reservations about Yvonne, and I was grateful not to be shut out of this part of her life.

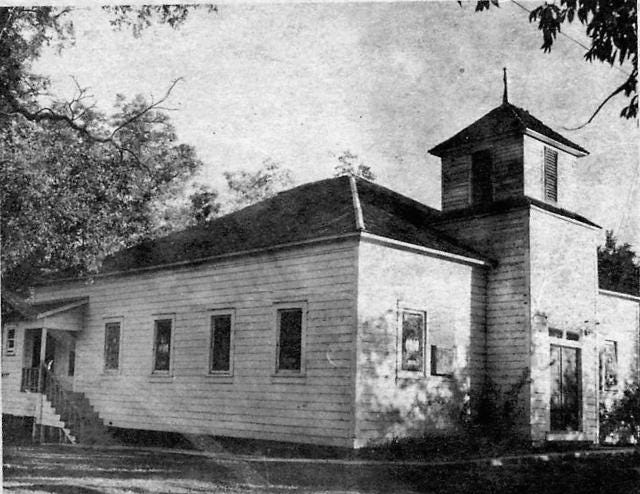

Neither of us had been to a black church before. When we arrived, the old frame building was already crowded and hot. Yvonne had saved seats for us near the front. I would have liked to sit somewhere less conspicuous, but it was reassuring to see that our presence was welcomed.

When the service began, the Pastor’s voice hit like a sledgehammer. The raw edge of grief was almost physically painful. He was sweating before he finished his welcome. We sang a gospel song I’d never heard before—full-throated, poignant, but agonizingly long. Following the words on the program, I was able to pick up the melody after a few bars and was incongruously grateful for the years I’d spent in the chapel choir at school.

Prayer followed. Then the eulogy. Several older family members began to wail. At the far end of the front row, I spotted a middle-aged man in a wheelchair. Cousin John, I surmised. His torso was shaking and his head gyrated in grief. The temperature rose, and so did the volume of voices. I felt sweat trickle down into my shirt collar. Out of the corner of my eye I could see Eileen swaying to the rhythm of the Pastor’s voice. Was that a tear welling up in her eye? It seemed like she was caught up in the grief of this large family, almost as if she were one of them.

After the funeral, there was a meal for the mourners. No one invited us, so we said goodbye to Yvonne and went out to the car. I was relieved to break free of the crowd. Not so Eileen. I could feel her disappointment on the silent ride home, and I remembered she’d told me after her father died, her mother had been estranged from the rest of the family. She and her mother and sister no longer saw them at Christmas or went to the beach with them in the summer. For a couple of hours inside that church, I realized, she must have felt like a part of Yvonne’s family, and now once again all the aunts and uncles and cousins had been taken away from her, and all she had left was me.

After that day at the church, something changed in Eileen’s attitude toward Yvonne. She didn’t talk about her as much as she used to. The phone calls were less frequent. Often when she called either no one answered or Yvonne was too busy to come to the phone. After they talked, she no longer fretted over this or that crisis in Yvonne’s life and whether she was going to be okay in the end.

I didn’t know whether to be relieved or worried about this change in Eileen. I was hesitant to bring up such a sensitive subject. At some level Eileen must be aware of my discomfort about the unequal friendship and the night trips across town. Asking her what changed, I was afraid, wouldn’t be taken an expression of sympathy.

I didn’t dwell on these thoughts. So much else seemed to be going well in our lives. We were cooking together, traveling together, making progress in school. We had friends. We enjoyed our new comrades. In the face of all this, a disagreement over a short-lived friendship with a self-centered teenager hardly seemed worth making an issue over. At age 22, I didn’t stop to consider that there might be more to this situation than just hurt feelings. I knew, of course, that her father had died, and I knew of her estrangement from his side of the family. In the excitement of living together, I just couldn’t see the hole in her life that this loss might have created, or grasp how painful it must be to see the hope of filling it slip out of her reach.

As I recall that time, I can see that she must have prepared herself for the ultimate disappointment that came some months later. She called Yvonne and got a recorded message saying the phone had been disconnected. It was a somber evening in our little apartment. After Eileen told me, I said I was sorry, but then she lapsed into silence and I didn’t know what more I could say. The last thing I wanted to do was let on I’d seen this coming from a long way away. In the stillness that night, I felt the weight of my own shortcomings. At the time it didn’t feel like a blessing, but looking back now I see that it was. A sense of our own helplessness is one of the tools God uses to lead us toward Him. This was something I’d rarely felt in my privileged young life. That night it moved me ever so slightly in the direction I was destined to go.