The final installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes in this series is available. Free subscribers will retain access until June 30.

The heart of man plans his way, but the LORD establishes his steps.

Proverbs 16:9 (English Standard Version)

During the six years I was a radical activist, almost none of what my comrades and I planned came to fruition. At every turn, it seemed I was either disappointed or thwarted. I didn’t recognize then, nor for many years afterward, that it was God who did this. But I did often suspect that something was going on behind the scenes that I couldn’t see. Though I didn’t know God, I sometimes wondered whether the twists and turns of my life were part of a plan that I wasn’t privy to. It wasn’t the kind of plan I feared would harm me. Quite the contrary: more often than not, the threats I most feared passed me by. But I did have an eerie feeling that someone was hunting me.

The immediate aftermath of radical activism did not bring enlightenment. Returning to New England at age 27, I felt drained and disoriented. The past, whenever I thought about it, was a bizarre kaleidoscope of confused ideas and emotions. I had a massive adrenaline hangover. I had seen miracles, but I didn’t yet recognize what they were.

I lived in a farmhouse in central Maine and taught in a small elementary school. It was a solitary existence. In my spare time—summers and school holidays—I tried to make sense of the activist years, but the memories were raw with emotion. Whenever I dwelled on them, I became agitated. Whoever I tried to describe them to was confused and uncomfortable. I tried to write them as fiction. They wouldn’t cooperate. Eventually I reached a point where I couldn’t stand to look back any longer. I buried the memories and moved on with my life.

God didn’t cease working inside me. The career I chose impulsively at age 20 turned out to be a far better fit than I had any right to expect. As teacher and educator I flourished. In Georgia, Maine, Iowa, and New York I taught students of all ages, from second graders to seniors in college to aged refugees learning English. I married. I earned a master’s degree, then a doctorate. I homeschooled my children. I became a professor. I was appointed department chair at universities in Minnesota and Illinois. For the past ten years, I’ve served as Dean in Ohio.

If you look at my resume, you’ll find no clue to the drastic change in my life. My credentials give no hint of what I did in my twenties. Even if you worked closely with me you would not see any obvious sign of the distraught Harvard student, the firebrand activist, the jilted and grieving husband, the regret-burdened turncoat. For five decades I rarely told anyone about my past. I rarely thought about what happened then. Once in a great while, usually when I traveled back to Boston to visit family, the memories would come back, and I would spend a few hours immersed in them before surfacing again with relief to the immediacy of the present.

I lived this fractured life, coasting along on the surface of tumultuous personal history, until the spring of 2017 when an extraordinary disruption forced me to recognize this wasn’t a path I could continue to follow. In my fifth year as Dean, at age 68, I was caught up in a crisis that pitted the local teachers’ union against our university president. It threatened to scuttle the teacher preparation program I was in charge of. Trapped between two powerful adversaries, I felt helpless. My allies could give me no help. I had no idea what to do or where to turn for support. A deep and paralyzing rage mounted inside me. I could barely focus on the routine tasks that kept everything running.

The crisis came to a head early one morning when I awoke at 4 am in a panic attack—heart racing, brain spinning out of control. I went downstairs to try to distract myself by watching yesterday’s news on TV, to no avail. The more I tried to distract myself, the more agitated I became at the thought of the firestorm bearing down on me.

I went outside to cool off. A bitter March wind was blowing. I took a long walk through the neighborhood, trudging up one street and down another as despair and revenge fantasies battled for control of my brain. When I finally got home I was drained and exhausted. I tried to eat breakfast but found that I couldn’t. I was shivering and trembling and sick to my stomach. I felt as if I were teetering on the edge of a chasm of despair that I would never be able to climb out of.

And then the dam broke. When had I last felt like this? The activist years. A wave of memories rushed back into consciousness: the paralyzing despair at Harvard, the fear of the draft, the confrontation with my father, the rage and belligerence at all those demonstrations and marches. The feelings of that time came thundering back, as vivid as if I were still living through it, a freight train of fear and aggression.

It was mid-morning when the attack finally ended. My mind cleared, and I was able to focus at work. I’d never experienced anything like this before. Flashbacks, I knew, are linked to PTSD, but what trauma had I experienced? I hadn’t been in a war or large-scale disaster. Reading about trauma, though, I learned that the pressure of protest—long-term exposure to fear and anger—could bring about the same type of response. The confusion I’d felt in the immediate aftermath was an early sign of post-traumatic stress. So were the unresolved anger and fear attached to the memories.

Burying memories is a common way to shield oneself from pain, but doing so also ensures that at a subconscious level the psychological wound festers. Eventually the painful memories will erupt, often triggered by an echo of the original traumatic experience. Being caught up in the dispute between the president and the city schools was the trigger for me.

How do we heal from trauma? I was relieved to learn the process isn’t esoteric or complicated. The regimen can be summed up in three simple words: time, talk, and safety.

Time, I realized, means time with the memories. If I wanted to heal, I couldn’t shut them away again.

Talk was what I’d missed back in New England, and what I’d avoided by burying memories. Recently remarried after a painful divorce, I now had someone to talk to. Trained as a chaplain and counselor, my new wife knew how to listen. Sharing our stories has become part of our life together.

Safety is a little less obvious. At one level it means being free of the original danger. I’d achieved that decades earlier when I broke from the activist movement. At another level it means having control over your life, which I did now. At a deeper level, though, it means a different kind of control that comes from understanding the past. My past was chaotic and deeply confusing. Reconstructing it, I realized, would not be the work of a day or a week or even many months. To prevent another eruption, though, the work had to be done. I sat down with pencil and paper and got started.

It was not easy work, but by this time I knew God. In The Back Road to Prayer, I explain how I developed this knowledge. It was an immense help as I sorted through those chaotic memories, trying to make sense of sequences of events that struck me at the time as strangely fortuitous. I now recognized that my intuition was right, that they were not random. There had to be some kind of plan behind them, and not a plan made by any of the flesh-and-blood people involved. Only God could have orchestrated all this, and if He did, his purpose was clear: to protect, teach, chasten, and guide me.

Five decades is a long way back to remember. The act of writing was painful. Reliving hatred, aggression, violence and threats of violence could be excruciating. I’d taken it all in stride at the time, but looking back I could scarcely believe something awful hadn’t come of it. Some days after an hour or two, I would feel a dark penumbra settling over me. I would have to put the writing aside. That night my wife and I would talk about what I had written and try to figure out what made it unsettling. Together we would usually make sense of it. The fog of depression would lift and I would sleep soundly.

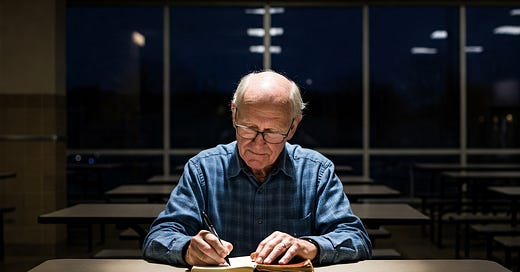

During this time she worked as a hospital chaplain. Several nights each month she was on call. Since she has difficulty driving at night, I would wake up with her and drive down to the hospital and wait in the cafeteria. There, while she comforted the bereaved and the dying, I would work on one of these episodes, laboriously rewriting each passage to extract a coherent narrative from the upwelling of anger and sadness. In the dead of night, the hospital was so quiet that I would become deeply absorbed in this work. So intense was my concentration that when my wife returned I would not see her approach. Only when she spoke to me would I know she was there.

As the trajectory of the narrative began to take shape, I thought often about how deeply that era had affected my life and how heavily the events of that time weighed on me. On one of our on-call nights this thought resurfaced after we got home and went back to bed. I was lying in the dark, drifting between waking and sleep and thinking regretfully how I had carried the legacy of that time—the anger, the panic, the loneliness—through five decades, more than two thirds of my life, when I heard a voice speak at the fringes of consciousness. A quiet voice, very distinct in the night stillness. It was a voice of infinite patience and love, yet also commanding. Small as it was, I could hear every word as if it were branded into my brain.

“Put down your burden.”

I knew who it was, but I did not know what I would be expected to do when I put down the burden.

“Come with me.”

I lay very still, transfixed by what I had heard, wondering whether I should say something to my wife. But of course this wasn’t the time. I could tell by the slow rhythm of her breath that she had just drifted off. She had had a hard night. Someone had died. Someone had grieved. This was her time to heal, not just mine.

So my mind turned back to the activist years. Freed of the burden of guilt and regret, I began to think differently about them. The loving tone of that voice at the border of consciousness reassured me. My eyes filled with tears at His acknowledgment of the weight I had carried so long. He knew me. He understood what I had been struggling with. And within the span of a few seconds He freed me.

But I still had a question—many of them, but one in particular that urgently required an answer. What in the world did “follow me” mean? Though gently delivered, it was a command that could not be ignored. To follow, though, one has to have some idea how and where.

By this time my wife and I were attending church. I met with the pastor to share some of the questions I still had about the Gospel, salvation, and Jesus. When I described my practice of prayer, he remarked that my conversations with God sounded rather one-sided. I spoke to God about my needs, but when did I listen? What he meant was that God speaks to us through scripture, and we should be reading it regularly.

Study of the Bible helped me understand what “follow me” meant. I began to see that God has a plan for the world, and that each one of us is part of the plan. Beyond a few brief, partial glimpses, we should not expect to understand fully the role we play. But that doesn’t mean we are left without guidance. The Bible is pretty specific about what we are to do in everyday life: love God and one another. Somewhere near the top of the list of how to love God was to remember what He has done for us. To do that we need to discern and remember.

What God did for me in my twenties—guiding, chastening, and protecting—is the most conspicuous evidence of His love that I have witnessed firsthand. Reflecting on that period of my life, I have noticed that my memories of it have a peculiar character. Laden with fear, anger, and grief, they are painful to remember. Yet that very fact also makes them exceptionally vivid.

Fifty years later I remember what everything looked and sounded like as clearly as if they took place yesterday. There is no danger of not being able to recall what happened then. There is no danger of not being able to see it clearly enough to discern God’s handiwork in my life. Once I had processed the emotions, there was no difficulty in writing it all down for other people to read.

In his letter to the Ephesians, the apostle Paul declared that we are “created in Jesus Christ for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (2:10, ESV). Does that not mean He decreed precisely this set of experiences, encoding them with emotion, so that I could later relive them and attest to them to whoever takes time to read what I’ve written?

So it is that the painful record of my youthful folly has become more than just the record of missteps of a brash young man seduced by a poisonous ideology and buried under an avalanche of lies. The story of my personal failings has been transformed into a celebration of God’s love and mercy. These episodes, harrowing at the time, have become pillars of faith I never expected to find.

Like every other believer, I have moments of doubt. I am susceptible to the materialist dogmas of the world, which claim it is foolish to believe in an unseen reality. When qualms like this surface, I have only to remember the great work God has done in my life to lay them to rest. Having publicly attested to what I have witnessed, I would be ashamed now to back down and deny it, however stridently those who insist that the material world is the only reality might demand that I do so.

Encounters with God is on break next week. Stay tuned—a new series launches May 30.

Wow. So much to say, enough to write an entire series, but I will refrain. For now. So much of your story struck home to me. I almost joined PL in my 20s, in the year 1970. (I am a bit older than you). Like you, I was a fervent atheist, and again, like you, I later realized the enormous role God played in my life back then. One difference is that I actually kept a diary for some of that period, including 1968, a tumultuous year. Recently I have begun thinking about a memoir, inspired by your work here, Charlie. Anyway, I am looking forward to what comes next in this space. Well, done, and thanks.