A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

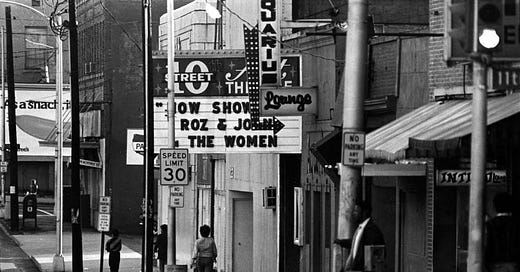

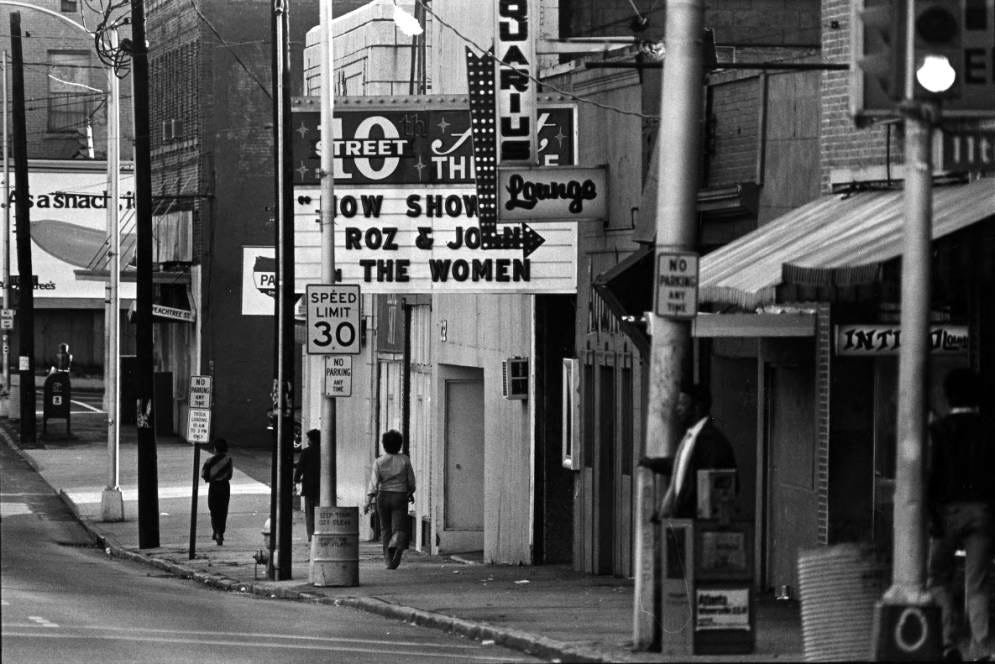

In 1971, at age 22, I traveled south from New England to help build up the Atlanta branch of a communist organization, the Progressive Labor Party (PL).

Joining the “Summer Project,” as Party leaders called it, was a spur-of-the-moment decision, motivated initially by my girlfriend Eileen’s desire to leave home and get out from under her mother’s restrictions, but it led to a flood of new learning neither of us anticipated, far beyond what I’d learned from college courses or any other part of my formal education. For Eileen and me, it was the first and only time we worked full-time for PL—an immersive experience beyond anything we’d gone through up to that point.

We’d hoped to rent our own apartment, but instead found ourselves living shoulder to shoulder with four other volunteers packed into three ground-floor rooms in a district of transients. A decrepit air-conditioner labored fitfully in the tiny kitchen. There was one bedroom and one bed, which our leader Peter shared with Rachel, his girlfriend. The rest of us spread out our sleeping bags in the living room. If you got up to go to the bathroom, you had to climb over inert bodies and make your way through the bedroom past Peter and Rachel.

Having lived in some fairly wretched rooming houses up north, I didn’t mind the cramped, grimy surroundings, but the lack of privacy was a huge burden. Finding a moment alone with Eileen was next to impossible. The closest thing to a date we I had in those months was to stuff our clothes into a bag and go out to a laundromat.

Outside the apartment, Atlanta wasn’t a great deal more hospitable. As white northern college students we stuck out wherever we went. We tried to dress like ordinary working-class Southerners, but everyone knew at a glance we didn’t belong and wondered what we were doing there. If they asked outright, no answer satisfied them. No one who spoke like us had relatives here or moved south for a summer job. The truth, which we did our best to conceal, was precisely what white Southerners suspected and feared. Memories of the civil rights movement were painfully fresh. The last thing they wanted was more white Northerners stirring up controversy.

In stores and restaurants, we were usually able to avoid open hostility. Not so at factory gates, where we sold Party newspapers at shift change. No possibility of disguising or even downplaying what we were there for. The Party demanded transparency. Every headline of that paper proclaimed the coming communist uprising. Every photograph showed angry blacks with clenched fists.

The antagonism at these factories was far worse than anything we’d faced in the North. Most weekday mornings we were up at 5 am so we’d arrive a full hour before shift change. I can still feel raw fear building in the silent car as we neared our destination. We were Yankees. We were the worst kind of Yankees, the kind who came down to stir up the blacks and create trouble. The real estate in front of plant entrances was a war zone.

Twenty yards out you could see the resentment and menace as workers approached.

What you hoped was for them to walk by you stone-faced and pretend you weren’t there.

Second choice: a terse brushoff. “Get that Yankee s*** out of my face.” “Get lost, ya f****** Commie.” “Get out of my way, n*****-lover.”

What you didn’t want was for one to stop and confront you. Every so often they would, especially if their pals were around.

“Try and sell me one of those papers.”

You’d try. They’d make a grab for it.

“How about I take those papers off you and stick them up your a**?”

“How about I go in there and get some of the boys to come out and clean this commie s*** out from in front of the plant?”

That was the whites—especially the older whites. With the blacks, different story. They liked what we said about fighting exploitation and racism. They liked the paper. They just didn’t want to be seen buying it.

At the steel plant, our preferred target, whites drove to work. Some of the older ones arrived very early, trickling in one by one from the parking lots. A worker by himself rarely gave us much trouble. As shift time grew closer, however, they started coming in clusters. This was when we were most vulnerable. Being in a group seemed to bolster white workers’ aggression, especially without blacks present.

Hiring blacks at the plant seemed to be a new development. Most were young and came by bus from the city, arriving ten minutes or so before shift change. The bus would hiss to a stop, the doors would clank open, and the workers would pile out and head toward the plant gates. We were always relieved when they got there. The whites never picked fights when the blacks were around.

Toward the end of the summer, we got a taste of just how much of a difference the arrival of those black workers made. The bus was late that morning. Kevin, a tall, skinny Harvard English major, was selling papers near the front gate. A group of whites approached. One of the older guys told him to leave or he’d “kick his skinny draft-dodging ass back to Russia.”

Kevin backpedaled. The guy lunged and grabbed for the papers. Just then the bus pulled up to the curb. The black workers spilled out. Kevin’s assailant got closer and spat in his face. Kevin froze. The assailant looked over his shoulder. He and his friends got very quiet. A group of young blacks approached, led by a tall, slender young man with hair braided in cornrows. He looked down at the whites with a kind of amused nonchalance.

“Y’all, did you see what this here cracker just done?” he called to his friends. “Spat on him, man. For real, spat on him!”

He grinned down, tilting head forward, as if inviting the older worker to take a swing. A crimson flush edged up from the white guy’s thick neck. Cursing under his breath, he turned and walked toward the plant.

Many a day afterward when we sold newspapers there we hoped and longed for that bus from the city to arrive early.

Miraculously, there was no violence that summer. As the weeks passed, we got used to the antagonism of white Southerners. It went with the life we had chosen. In an odd way, it may have validated that life. If we were as much of a threat as all those white Southerners seemed to believe, then the sacrifices we were all making—conventional middle-class careers, free time, normal social relations—must not be in vain.

This new perspective on our life choices raised a question for Eileen and me. What would adult life be like for a radical activist? As college students we had the free time and the flexibility to attend protests and meetings, sell newspapers at factory gates, and take a summer off to follow our comrades. After we graduated and got full-time jobs, the rhythm of life would be different. What would commitment to the cause look like when work and home played a larger role in our lives?

The Party members in Atlanta, whom we had traveled down here to help, had all either finished college or expected to graduate soon. They were building lives here, and so we saw them as models for our own future selves. In addition, like us, none of them were native Atlantans. I was curious to see what they’d done to fit in in a place where they’d moved for the express purpose of preparing for communist revolution. Were they accepted by neighbors and co-workers? Had they made friends? Did they belong?

The Party acknowledged this difference between the two groups. We summer volunteers were cautioned not to “hang out” with local members and encroach on their time. The two groups met infrequently; we saw the locals only at Party events, never among their own friends. Still, it was hard not to speculate about how well they adapted to their new lives, and often our insights proved to be valid. Since Eileen and I remained in Atlanta after the summer ended, we maintained contact with most of the comrades and were able to observe their involvement at close quarters.

One would have thought a stable relationship between two Party members would strengthen their long-term commitment, but that turned out not to be true for the two couples in the Atlanta branch of the Party.

The first of these couples, Stan and Dee, were still in college that summer and fall, so it was hard to get a good read on their long-term trajectory. After graduating, they married and moved North to be near Stan’s family. Soon after the birth of their first child, I visited them there and found them busy with family and no longer active. Today, based on social media, they appear to be active in local causes but are no longer affiliated with PL or any other radical group.

The second couple, Ian and Frankie, had already graduated and were working full time, but they didn’t last long either. Even that summer I had doubts about how well they fit in. Ian, a Harvard graduate, worked as a medical technician. With his Northern accent he would never have passed for an ordinary Atlantan. His narrow thoughtful face and fine longish blonde hair exuded upper middle-class refinement. Frankie, short, blonde, and vivacious, daughter of a well-to-do family in Tampa, had led a radical organization at Florida State and now taught in a school for deaf children. Though she claimed to have shed her family’s wealth and social position, her origins radiated through her cheerleader personality. It was hard to imagine either Ian or Frankie at ease among the working-class people we were trying to recruit. Both left the Party within a year after we met them, and thanks to Frankie’s affair with a fellow teacher, their marriage dissolved soon thereafter.

Another teacher, Nora, led an even more irregular personal life. A soft-spoken Radcliffe graduate, she taught English literature at one of the toughest city high schools, where she had affairs with two of her students, both of whom, at different times, lived with her. She disappeared at the the end of that first summer, and none of us heard from her after that. Nearly 50 years later, I heard that she’d married, presumably not to one of her students, and was now a grandmother with a large family. No mention of any involvement in radical politics.

Nick, a Russian immigrant, was the oldest of the group. He was married to Jan, who was not politically active. He had a master’s degree in history but now worked as a laborer in a specialty steel plant. I encountered him only once, briefly, at one of our meetings. He seemed aloof, preoccupied, set apart from the rest of us. Over the next few years, he drifted away from the Party, and finally broke contact entirely. None of us saw him again, though we heard he was teaching at a college in Connecticut.

Although all of these members were loyal to PL and believed what it stood for, I could not see in them the kind of transformation I hoped to make in my own life. Stan, a former GI, better exemplified the person I was trying to become, though the path he had chosen was not one I thought I could follow.

Despite being a college student, eligible for a deferment, Stan had allowed himself to be drafted into the Army so he could organize resistance on the inside. This bold initiative had had heart-breaking consequences. Soon after he began organizing fellow GI’s, he was imprisoned in a stockade, where he contracted tuberculosis, before being court-martialed and dishonorably discharged.

Here in Atlanta, he was undergoing treatment that depleted his energy, leaving him unable to work or go out selling newspapers. He did come to meetings, though, where he spoke with an air of quiet authority. Unlike the others, who alongside their activism had made normal progress in middle-class lives, Stan had made a tangible sacrifice. In his slow speech and stolid demeanor, I could detect no trace of his middle-class origins. I guessed that when he recovered he would have a better chance than the others of making a life for himself here as a Party loyalist.

In Stan, I saw the destination I hoped to reach, but I could not see myself taking the same route to get there. At one time I had considered allowing myself to be drafted so I could organize inside the armed forces. In light of Stan’s experience, I was glad now that I hadn’t. I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to go through what Stan had endured. It wasn’t something anyone would choose willingly, Party member or not.

There was, however, one other comrade in whom I could see glimpses of my own future life. Irma Jean, a corpulent redhead in her late twenties, led the Atlanta Party group. Her blunt, assertive, but humorous approach perfectly fit what I conceived to be the role of working class leader, and I was intensely curious about how she had cultivated this style.

She grew up in a lower-middle class home in a small town in South Carolina. She’d gone to college, earning a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, which must have been a considerable sacrifice for her parents, a postal worker and a stay-at-home mother. She then moved on to divinity school in New York, where she got caught up in radical politics, eventually joining the Party.

Somewhere along that journey, she had radically transformed her personal style. When I met her she wore bright sleeveless shifts that showed large expanses of pink flesh and looked like they didn’t get laundered too often. Her Southern drawl was loud and sarcastic and sprinkled with obscenities never heard from genteel Southern women, let alone someone who’d studied in Divinity School. At one of our gatherings when somebody mentioned the taunts of the white steelworkers, she chuckled incredulously and retorted,

“Stomp the living s*** out of one of those guys, and the others’ll leave you alone.”

At the ripe old age of 22, I took that as wisdom and courage—a kind of miracle for a woman who’d grown up in a small southern town. I longed to know what happened to her in New York, what brought her into radical politics, and how she’d managed to eradicate every trace of her upbringing, as I hoped to do mine. Looking back, I suppose the logical thing to do would have been to just ask her, but I could never have done that, and not just because she was a Party leader and I an awkward and inexperienced acolyte. In those days we were all a little ashamed of where we had come from. None of us wanted to dwell on how we arrived where we were now.

My attraction to Irma Jean as a moral exemplar, I now realize, was prescient. Like the Summer Project and Atlanta itself, she had something to teach me, but it was not, as I thought at the time, about how to become an exemplary Party member. What I learned from Irma Jean came from an entirely different source.

Having known Christ in the past, Irma Jean still belonged to Him. She was His lost lamb. Through her He spoke to me, first to warn me about sin. Alas, I ignored that message. I sinned grievously.

Later, however, I was given another chance. By the misfortunes that eventually befell Irma Jean, by the sadness and loss that awaited the would-be leader of the great proletarian uprising, I came to see the calamity that awaited me in my my own life if I didn’t change course.

A half-century later, I can still feel the weight of her sadness, along with the chill of our parting when I belatedly learned the lesson set by the Lord and drastically changed the course of my life, leaving the Party and breaking ties with my comrades. I still dream of finding out what became of her, all these years later, but alas her real name is more common than the one I’ve given her here, and all my efforts have resulted in failure. If I could find her, and if she would forgive me for deserting the cause, I would like to thank her for helping me find my way to the One whom she knew and, sadly, rejected.