A new installment of Hunted, an autobiographical account of God’s action in the life of a Vietnam War era radical activist. New to the series? This introduction provides context for the events described here. An index of other episodes, updated monthly, is also available.

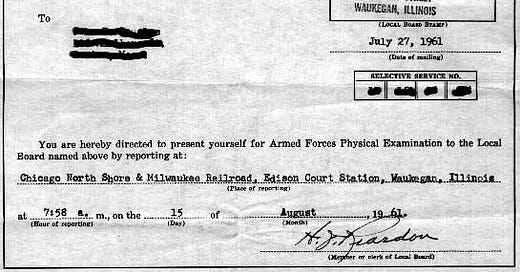

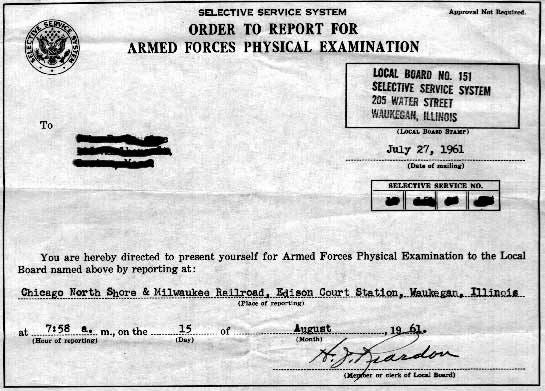

Even though my visit to Bryant College, described in the last episode, contributed little to the radical movement, my confrontation with the military recruiter there reverberated far beyond the peace and contentment that I felt in the immediate aftermath. A couple of weeks later I received a notice from the Selective Service System that my draft classification had changed to 1-A (eligible for service). I was directed to report to a military intake facility for a physical examination.

I wasn’t worried about being drafted—not right away at least. Selective Service had adopted a lottery system based on numbers assigned randomly to birthdates. My number was in the low 300’s out of 365. 5/6 of draft registrants would be called up before me.

Even so, being reclassified was a momentous event for every college student in the Vietnam War era. When I’d dropped out of college a year ago, I’d requested a 1-Y, a year-long medical deferment. I’d never received it. Now that I was 1-A, the obvious move would have been to request renewal of the 2-S, since I was in school again.

Before I became a radical activist, I would have done this without hesitation. For a campaigner for justice, though, it would have been hard to justify. Kids who went straight to work after high school weren’t eligible for any deferment. In fact the entire draft system, which offered middle-class kids a way to avoid service, was a prime example of the class privilege our movement was supposed to be fighting to eliminate. It would have been hypocritical, to say the least, to campaign for a socialist revolution while clinging to the spoils of the capitalist system.

Avoiding hypocrisy wasn’t my only reason for not seeking a student deferment. PL, the communist group I was involved with, encouraged its followers to join the military, either by enlisting or by allowing themselves to be drafted. Inside the armed forces would be the perfect place to stir up dissension and build our movement. How could working-class enlisted men, especially blacks and Hispanics soldiers, not gravitate to the message of communist revolution? Stories abounded of GI protests, desertion, and “fragging” (enlisted men killing officers). PL leaders anticipated that these rank and file service members would one day join workers on the outside in a mass movement to overthrow the government, seize power, and abolish the capitalist economic system. The Party already had a small underground network of organizers working feverishly for our cause. To join in this effort would be a badge of honor, evidence of extraordinary commitment. Conversely, trying to avoid doing so might be considered a token of apathy or even cowardice.

On the date of the physical, I took a bus out to the intake facility. It was a sunny day in early May, unusually warm. Trees along the bus route were just beginning to blossom, but I was only vaguely aware of them. Going into the military to organize for PL would be a huge step forward for me as an activist, but could I pull it off? Would I have anything in common with my fellow GI’s? Would they take me seriously? Was there any way to do this and not be found out by the brass (officers)? What did they do with communist agitators in the armed forces?

Wrapped up in these thoughts, I barely noticed my surroundings until the bus pulled up to the intake facility. A couple of other young men got off. I followed them inside. I wasn’t looking forward to the physical exam, but it was nothing compared to what it would be like to serve in the military as a communist organizer. Ordinarily I would have hated being ordered to strip to my underwear and join the long line of nervous registrants, but on this day I barely noticed. When it was time to be poked and prodded, the exam turned out to be milder than I expected, verging on perfunctory. I was still bracing myself for something worse when I was told we were done and I could put on my clothes.

Fully dressed, I followed the line of young men to the exit station to check out. When my turn came, however, this turned out to be no mere formality. Everyone else had been dismissed with a nod and a scrawl on a form, but in my case there was someone else to report to. I was led out of the big gymnasium-like room where we’d been examined, down a dimly-lit hallway, and into a windowless office with a desk and a couple of chairs but no other furniture.

Behind the desk sat a heavy-jowled man wearing civilian clothes—a rumpled sport jacket but no tie. I remember thinking it didn’t look like he belonged here. Was it the clothes? The sparse furnishings? The silent departure of my escort, without acknowledging him?

The man behind the desk motioned me to a chair. There was a file in front of him. He took his time opening it. Finally he took out a sheet of paper and spent a few minutes reading. I couldn’t make out the text, but I spotted a college insignia at the top and realized it was the letter from the psychiatrist recommending me for a temporary deferment.

He asked if I knew what it was. I nodded and tried to explain. The letter had been written over a year ago. I’d been under severe stress then. The stress was gone now. I was 100% cured. Doing just fine. Back in school.

The mysterious man took all this in without moving a muscle. It was hard to read him. Did he believe me? Had he even processed what I said? Did he know more than he was letting on?

When I was finished he looked at the letter a few more seconds, and then asked patiently if I was applying for a student deferment. I told him I wasn’t. If called, I would serve.

He stared at me. This wasn’t the answer he was looking for.

“You’re getting a deferment anyway.”

“I’m not applying for one.”

“You don’t need to.”

The deferment had already been issued. A permanent deferment. Not the year-long stopgap I’d asked for the year before. This one was forever. He took a sealed envelope out of the folder and handed it to me.

I asked sharply what evidence this action was based on. The man stared. I could feel the tiny eyes boring into me as he considered my challenge. Then, very slowly, he pushed his chair back and stood up, and I realized he wasn’t going to answer. There was nothing more to be said. We were finished. He wanted me out of the room.

Fingering the envelope, I stepped out into the dim hallway and tried to remember which way I had come in. I knew intellectually what had just happened, but the reality hadn’t hit me yet. None of it made any sense. Who was this guy? He didn’t dress like he was military. What business did he have in that office? What connection did he have with Selective Service? The draft board where I’d registered was in a suburb of Boston, 60 miles away. How did he get hold of that letter?

I was outside now, blinking in the late afternoon sunlight, oblivious to the sweet spring air. Selective Service. The draft board. The U.S. Government. The sheer institutional power of these entities was overwhelming. They had no reason to do what they’d done. They had no reason to notice me. Unless—

Walking slowly back to the bus stop, I thought back over the past few months: getting thrown out of the college President’s office, organizing the rally for the fired mechanic, humiliating the military recruiter at Bryant. Every one of these actions had threatened somebody powerful. The powerful people must have noticed. But did they notice me? Had they connected the threat of our movement to my name, my social security number, and my draft file?

Back in March, when we first discussed the possibility of an informant among us, the idea that someone would go to the trouble to track us had seemed far-fetched. Not now. Whoever the guy in that office was, he knew more about me than just what the psychiatrist said in his letter. One year. That was all he had recommended. Selective Service would never have issued a permanent deferment based only on that.

The bus back to college was nearly empty. I sat there in a fog, staring out the window at the verdant spring shrubbery. The smell of trees in bloom in the warm air was intoxicating. I was still having trouble believing what had just happened to me. The thought that someone I could not see was watching me was disconcerting. Not knowing who it was was bizarre. But what was even stranger was what they had done. Was I such a great threat that someone would go to all this trouble to keep me out of the Army? Did they have any idea that in doing so they’d saved me from the two things I most feared—singlehandedly confronting the army as a communist agitator, and having to kill innocents to save my own life?

It didn’t occur to me in those days that whoever was watching me might have orchestrated all this not to protect the Army from me, but to protect me from the Army. Or that whoever that was had a plan for my life that had nothing to do with building a mass movement to smash capitalism. Many more years would pass before I could see that I had been kept safe that day for an entirely different purpose. At the time I knew only that something very odd and unexpected had happened and because of it I had been spared from something awful.

Wow, what a recollection and very well written. The encounters with powerful institutions over whole we have no sway or influence is traumatic, regardless of how they turn out. Glad you were spared ,and thank you for recording your story for posterity. What a time to be alive that was!